Patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation receive high doses of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, which cause severe immunosuppression.

ObjectiveTo report an oral disease management protocol before and after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

MethodsA prospective study was carried out with 65 patients aged>18 years, with hematological diseases, who were allocated into two groups: A (allogeneic transplant, 34 patients); B (autologous transplant, 31 patients). A total of three dental status assessments were performed: in the pre-transplantation period (moment 1), one week after stem cell infusion (moment 2), and 100 days after transplantation (moment 3). In each moment, oral changes were assigned scores and classified as mild, moderate, and severe risks.

ResultsThe most frequent pathological conditions were gingivitis, pericoronitis in the third molar region, and ulcers at the third moment assessments. However, at moments 2 and 3, the most common disease was mucositis associated with toxicity from the drugs used in the immunosuppression.

ConclusionMucositis accounted for the increased score and potential risk of clinical complications. Gingivitis, ulcers, and pericoronitis were other changes identified as potential risk factors for clinical complications.

Pacientes submetidos a transplante de células hematopoiéticas recebem altas doses de quimioterapia e radioterapia que podem causar imunossupressão e doenças orais graves.

ObjetivoApresentar um protocolo de avaliação de doenças orais antes e após transplante de células hematopoiéticas.

MétodoEstudo clínico prospectivo de 65 pacientes com idade acima de 18 anos, com doenças hematológicas submetidas a transplante de células hematopoiéticas, divididos em dois grupos: A (transplante alogênico, 34 pacientes) e B (transplante autólogo). Foram realizadas três avaliações odontológicas: período antes do transplante (momento 1), uma semana (momento 2) e 100 dias após o transplante (momento 3). Em cada momento as alterações orais foram pontuadas e classificadas como leve, moderada e grave.

ResultadosAs alterações orais mais frequentes foram: gengivite, pericoronite do terceiro molar e úlceras. Entretanto nos momentos dois e três a principal doença foi a mucosite associada a toxicidades das drogas usadas na imunossupressão.

ConclusãoMucosite foi principal alteração, com a pontuação mais alta e com maior risco de complicações. Gengivites, úlceras e pericoronites foram outras alterações com risco menor de complicações.

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is the replacement of a diseased or deficient bone marrow by normal cells, with the aim of reconstituting the marrow and providing immune system control. It is classified as autologous when bone marrow precursor cells come from the patient, and as allogeneic, when the cells come from another person (donor), who may or may not be related to the recipient.1,2

Patients who will undergo HSCT are submitted to high doses of chemotherapy and radiation therapy to eradicate the underlying disease, which induces an intense immunosuppression period known as the conditioning phase. This period is characterized by possible tissue damage and infections due to immunosuppressive drug toxicity.3–5

Mucositis is one of the most common oral tissue lesions described in these immunosuppressed patients, caused by the toxicity of these drugs; it results in a fragility of the oral mucosa with decreased numbers of basal cells, and even the onset of ulcerations.6–8 It is considered the most important oral cavity complication in patients undergoing bone marrow suppression, and is also the most common, with an incidence of 90%.9,10 Kolbinson et al.11 described early changes in the oral mucosa such as erythema, ulceration, and epithelial pseudomembrane formation that appear between five and seven days after the onset of chemotherapy and improve after three weeks.

These lesions represent a significant risk factor for systemic infections, particularly in patients with neutropenia, and 20–50% of cases of septicemia originate from the oral cavity.12–14 For Puyal et al.,10 Köstler et al.,15 and Yamagata et al.,16 the rates of occurrence of oral lesions varied, depending on the type of underlying disease, the treatment used and oral status before conditioning for transplantation, and reflected mainly pre-existing oral conditions.

Lesions such as root fragments, periodontal pockets, periapical lesions, and removable dentures are considered reservoirs of opportunistic pathogens that can trigger infections during immunosuppression.9,17–19

These reports indicate that the prevention of oral disease prior to HSCT is extremely important and that oral diseases should be treated before transplantation to eliminate potential risk factors for systemic infections.7,20–22 Dreizen et al.22 reported that 30–50% of patients undergoing chemotherapy for oncologic treatment develop oral alterations or lesions, and that incidence can be significantly reduced by prior oral intervention. However, we found few studies in the literature, except those for mucositis, which attempted to quantify oral alterations that occur in patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation. When the authors, applied a score to the condition, they eliminated the subjective nature of the potential of these alterations for clinical complications.3,7,8,23–30 Thus, the objective of this research was to develop a standardized method for the quantitative evaluation of alterations or lesions of the oral cavity, and to identify the potential for clinical complications in patients submitted to HSCT.

MethodsThe present study was a clinical, prospective, six-month longitudinal temporal cohort study, with a data collection period of 24 months, performed at a referral hospital. The study was approved by the local research Ethics Committee (No. 39/2007). A total of 65 patients aged>18 years, of both genders, with or without hematological malignancies, who underwent HSCT and immunosuppression in the abovementioned period were included. Patients were grouped according to the type of HSCT: group A (allogeneic), 34 patients; and group B (autologous), 31 patients. Initially, all answered a questionnaire, which contained information on oral health and oral hygiene habits. Subsequently, the patients were evaluated according to the status of the oral cavity at 20 days, on average, before conditioning and HSCT (moment 1). The second evaluation was carried out in the first week after transplantation (moment 2), and the last evaluation 100 days after HSCT (moment 3).

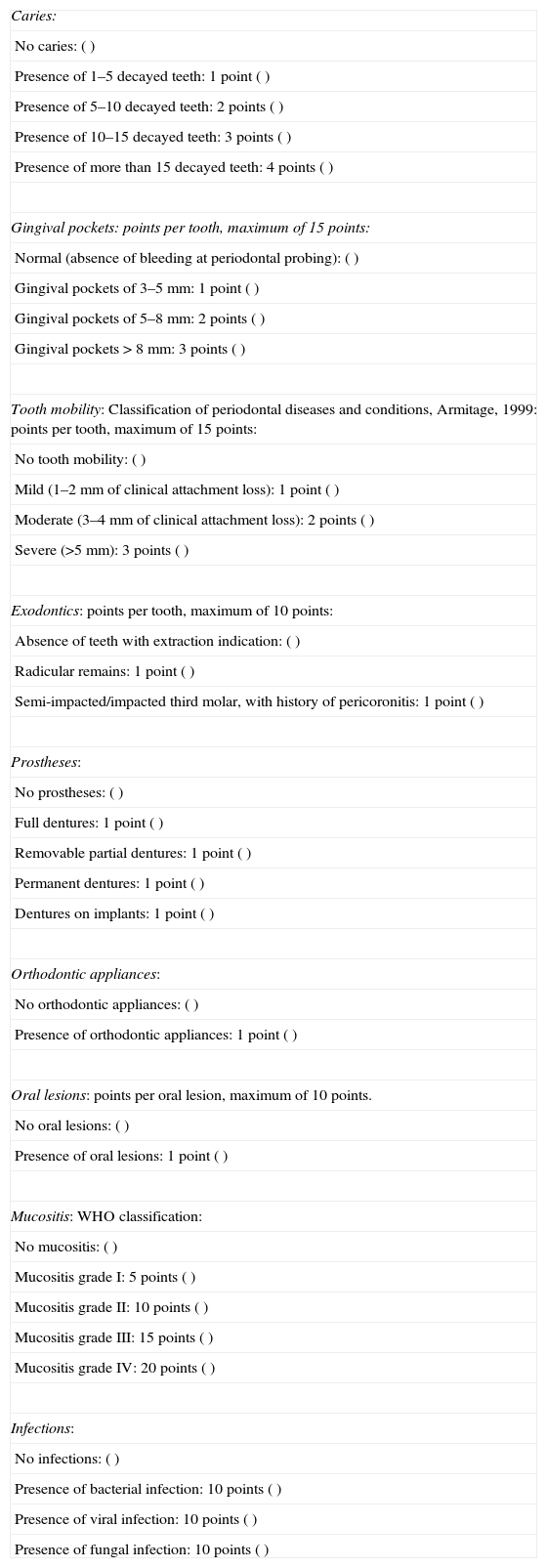

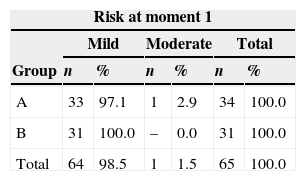

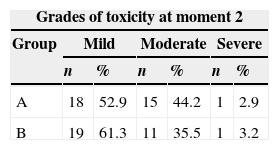

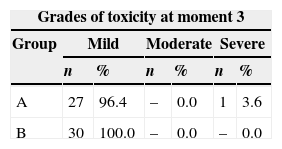

At the evaluation moments (1, 2, and 3) scores were given to the different alterations found in the oral cavity, according to the proposed dental standardization (Table 1). The score given to the oral alterations was based on previous work, which gave greater or lesser degree of importance to the histopathological alterations of the oral cavity.3,7–10,14,24 The risk classification and degrees of toxicity were based on the work of Porak,14 Dreizen et al.,22 and Parulekan et al.24 In moment 1, patients were classified according to the risk for complications: mild (up to 15 points), moderate (16–30 points), and severe (31–50 points) risk. In moments 2 and 3, the degrees of toxicity were classified as follows: mild (15 points), moderate (16–30 points), and severe (31–50 points; Table 1).

Data standardization form with scores related to changes in the oral cavity.

| Caries: |

| No caries: () |

| Presence of 1–5 decayed teeth: 1 point () |

| Presence of 5–10 decayed teeth: 2 points () |

| Presence of 10–15 decayed teeth: 3 points () |

| Presence of more than 15 decayed teeth: 4 points () |

| Gingival pockets: points per tooth, maximum of 15 points: |

| Normal (absence of bleeding at periodontal probing): () |

| Gingival pockets of 3–5mm: 1 point () |

| Gingival pockets of 5–8mm: 2 points () |

| Gingival pockets>8mm: 3 points () |

| Tooth mobility: Classification of periodontal diseases and conditions, Armitage, 1999: points per tooth, maximum of 15 points: |

| No tooth mobility: () |

| Mild (1–2mm of clinical attachment loss): 1 point () |

| Moderate (3–4mm of clinical attachment loss): 2 points () |

| Severe (>5mm): 3 points () |

| Exodontics: points per tooth, maximum of 10 points: |

| Absence of teeth with extraction indication: () |

| Radicular remains: 1 point () |

| Semi-impacted/impacted third molar, with history of pericoronitis: 1 point () |

| Prostheses: |

| No prostheses: () |

| Full dentures: 1 point () |

| Removable partial dentures: 1 point () |

| Permanent dentures: 1 point () |

| Dentures on implants: 1 point () |

| Orthodontic appliances: |

| No orthodontic appliances: () |

| Presence of orthodontic appliances: 1 point () |

| Oral lesions: points per oral lesion, maximum of 10 points. |

| No oral lesions: () |

| Presence of oral lesions: 1 point () |

| Mucositis: WHO classification: |

| No mucositis: () |

| Mucositis grade I: 5 points () |

| Mucositis grade II: 10 points () |

| Mucositis grade III: 15 points () |

| Mucositis grade IV: 20 points () |

| Infections: |

| No infections: () |

| Presence of bacterial infection: 10 points () |

| Presence of viral infection: 10 points () |

| Presence of fungal infection: 10 points () |

Evaluation results were compared among themselves and between groups. For the variables gender, age, disease, drugs for conditioning, cell source, and type of transplantation, the chi-squared or Fisher's exact test were used for comparison of the groups. For the variables dental caries, gingival pockets, tooth mobility, tooth extractions, dentures, orthodontic devices, oral lesions, bacterial, viral, fungal infections, and mucositis, the Mann–Whitney test was used. Comparison between groups at each evaluation was performed using Friedman's test and comparison of moments within each group was performed using Fisher's test. The level of significance was set at 5% (p<0.05).

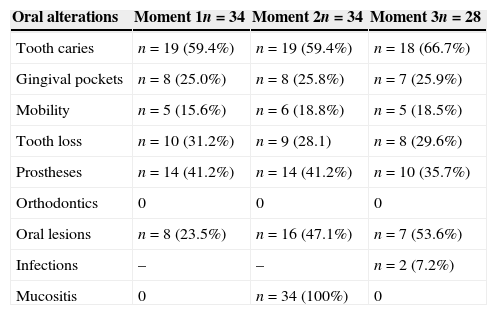

ResultsAfter the assessment of oral alterations, the classification of risks and toxicity of patients was performed by summation of the scores (Tables 2–4). In the first assessment, before conditioning, most patients received a mild risk classification in both groups. The only patient classified as having moderate risk had gingival pockets>6mm and tooth mobility; that patient's score was>16 (Table 5).

Distribution of oral abnormalities observed in subjects from group A.

| Oral alterations | Moment 1n=34 | Moment 2n=34 | Moment 3n=28 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tooth caries | n=19 (59.4%) | n=19 (59.4%) | n=18 (66.7%) |

| Gingival pockets | n=8 (25.0%) | n=8 (25.8%) | n=7 (25.9%) |

| Mobility | n=5 (15.6%) | n=6 (18.8%) | n=5 (18.5%) |

| Tooth loss | n=10 (31.2%) | n=9 (28.1) | n=8 (29.6%) |

| Prostheses | n=14 (41.2%) | n=14 (41.2%) | n=10 (35.7%) |

| Orthodontics | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Oral lesions | n=8 (23.5%) | n=16 (47.1%) | n=7 (53.6%) |

| Infections | – | – | n=2 (7.2%) |

| Mucositis | 0 | n=34 (100%) | 0 |

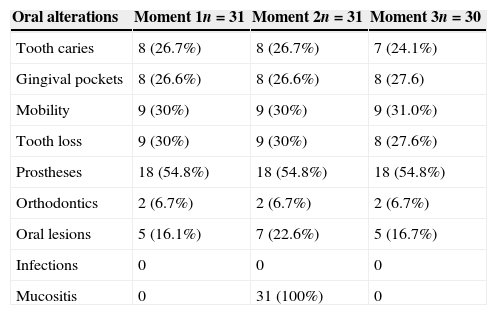

Distribution of oral abnormalities observed in subjects from group B.

| Oral alterations | Moment 1n=31 | Moment 2n=31 | Moment 3n=30 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tooth caries | 8 (26.7%) | 8 (26.7%) | 7 (24.1%) |

| Gingival pockets | 8 (26.6%) | 8 (26.6%) | 8 (27.6) |

| Mobility | 9 (30%) | 9 (30%) | 9 (31.0%) |

| Tooth loss | 9 (30%) | 9 (30%) | 8 (27.6%) |

| Prostheses | 18 (54.8%) | 18 (54.8%) | 18 (54.8%) |

| Orthodontics | 2 (6.7%) | 2 (6.7%) | 2 (6.7%) |

| Oral lesions | 5 (16.1%) | 7 (22.6%) | 5 (16.7%) |

| Infections | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mucositis | 0 | 31 (100%) | 0 |

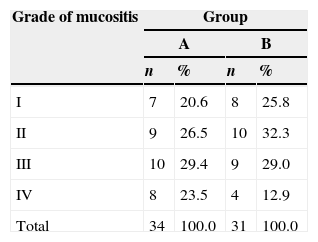

In the second evaluation, of the 34 assessed patients in group A, 18 had mild toxicity, 15 moderate, and one patient had severe toxicity. In group B, of the 31 patients assessed, 19 had mild toxicity, 11 moderate, and one patient had severe toxicity (Table 6). As it can be observed, the risk and toxicity classification in both groups were performed according to the presence of mucositis and its degree of severity.

In the third evaluation, as a result of deaths, 28 patients were assessed in group A and 30 patients in group B. All but one patient had mild toxicity in this assessment, and one patient persisted with severe toxicity (Table 7).

No statistical differences were observed regarding the scores in both groups A and B, for the variables dental caries, gingival pockets, tooth mobility, tooth extraction indication, dentures, and orthodontics in the three moments (Tables 2 and 3). Comparing the moments of assessment within the groups, it was observed that there was no statistically significant increase in oral mucosal lesions over time within group A (p=0.039). However, a statistically significant difference was observed when comparing moment 2 of groups A versus B, as mucositis was observed in 100% of individuals in both groups at these moments (Tables 2 and 3).

DiscussionHSCT is a widely used therapeutic technique, aiming to cure oncologic patients and to provide disease control.1 However, conditioning with chemotherapy drugs can result in several oral and systemic alterations in immunosuppressed patients.3–6 These manifestations can increase the length of hospital stay, increase treatment costs, and directly affect the quality and quantity of life of these patients.25

In the autologous HSCT, comorbidities occur most often due to the underlying disease activity, whereas in allogeneic HSCT, they are due to systemic complications and the graft versus host reaction itself.1,2,17,30 The intense immunosuppression predisposes transplanted patients to severe infections that can occur at any time of transplantation, can be caused by different etiological agents such as bacteria, fungi, viruses, or parasites.13,21

Establishing risk factors by assessing the status of the oral cavity and systemic complications of HSCT, and by assigning scores to the alterations at different times of the clinical follow-up of patients submitted to immunoexpression might facilitate the identification of individuals who would potentially have more clinical complications.8,16 A quantitative analysis using scores eliminates the subjective nature of the observations.24 In the present study, the development and utilization of scores for oral alterations were based on previous studies that sought to associate, through scores or degrees of intensity, what changes or oral diseases associated with transplantation would, in theory, have greater potential to be associated with clinical complications.14,16,19,22,24

The creation of tables and dental records was made based on the following variables: dental caries, gingival pockets, tooth mobility, root fragments, tooth extraction indication, use of dentures, orthodontic devices, and oral lesions.

Alterations also included the specific complications of HSCT, such as the occurrence of bacterial, fungal and viral infections, as well as the degree of mucositis.8,14,22

With respect to dental caries, the present data and those in the literature showed no significant increase in new dental caries in patients in the post-transplantation period and, as they are not relevant to HSCT complications, they have minimal score.

The gingival status and tooth mobility have a potential risk factor for complications, especially periodontal pockets greater than 6mm.26,27 Gingival pockets of this size favor greater accumulation of bacteria and necrotic tissue, and increase the risks for dental and oral disease; therefore, they received scores of up to 15, with intermediate values between dental caries and mucositis.

In both groups of the present study, only one patient had larger gingival pockets, ranging from 5mm to 8mm, and was classified at moment 1 as moderate risk and at moments 2 and 3 as severe toxicity, due to the presence of deep gingival pockets.

Another common observation, in approximately 80% of the patients, was gingival hyperemia, probably due to toxic reactions to drugs used during conditioning. Another likely cause is oral mucosa sensitization due to antiseptic mouthwash (chlorhexidine) used in oral hygiene. Patients do not brush their teeth for fear that trauma caused by the brush can cause bleeding, due to thrombocytopenia.

However, the lack of brushing can result in an increase in bacterial plaque, causing gingivitis, such as that seen in individuals at moment 2 in both groups, with a consequently greater risk of bleeding. When there is gingival inflammation, plaque can form more rapidly in those sites than in non-inflamed ones and thus, mouthwash would be less effective for oral hygiene. However, in the present sample, these alterations were barely observed, which was attributed to more effective actions before transplantation by the treating institution.1,2,10,16,17

Findings such as tooth extractions and semi-impacted third molars with a history of pericoronitis are mentioned in the literature as having little potential as source of opportunistic pathogens and, as they were seldom observed, they were not scored.21–23

Semi-impacted third molars were observed in eight patients from group A and nine from group B. At moment 2, together with mucositis lesions, there was formation of plaque and gingiva overlying the tooth. For this type of finding, and for prostheses and orthodontic devices, 1 point was scored. Shulman et al.28 reported that orthodontic devices and dentures are risk factors for stomatitis.

Even with the knowledge of this report of possible health risks for individuals wearing prostheses, it was not possible to establish statistically significant data correlating them with oral alterations.29 But since we knew that the oral cavity is the gateway of infections in patients undergoing immunosuppression for bone marrow transplantation and that the use of orthodontic devices and dentures can potentiate them, we asked our patients not to wear them, if possible.21 These recommendations were made before the first evaluation, and were the reasons for the paucity of alterations at moment 1. Although that was not the purpose of this study, we demonstrated the importance of prevention and treatment of oral diseases to lessen the risk of clinical complications in immunosuppressed individuals.8,21 This was also the opinion of Sonis and Kuns,23 who showed a decrease in these complications when such care was performed.

Some non-infectious oral lesions, such as oral leukoplakia, gingival hyperplasia, and others that are seldom described by other authors, also infrequently were observed by the present authors. Oral lesions similar to hemorrhagic lesions that were difficult to characterize, but did not evoke clinical complaints were observed in 17 patients from group A and eight patients from group B at moment 2, caused perhaps by thrombocytopenia; these were resolved in moment 3.

The literature documents that mucositis is unquestionably the oral alteration that is the main risk factor for the systemic infections that occur in between 20% and 50% of HSCT patients, most prevalent in those with associated neutropenia.3,5–10,19–21 The intensity of mucositis can vary depending on the underlying disease and the type of transplantation, as well as the oral status before and during immunosuppression.11,14,15

In the present study, the incidence of mucositis was 100% in the second evaluation, at moment 2, for both group A and group B patients. The risk association of moment 2 and mucositis was significant. Both groups showed an association of the risk classification and/or toxicity (mild, moderate, severe, and very severe) with the onset of mucositis and degrees of intensity. Most patients were classified as having mild risk, but those who developed mucositis were classified as having moderate or severe risk.

These patients also had oral lesions, more often on the tongue and labial mucosa, characterized as erythema of the oral mucosa, lichen planus, generalized erosions, ulcerations, and xerostomia.30

Some authors reported that this is due to low oral food intake, because of pain caused by these lesions.18,21,25 In the present study, this observation was more evident, as 15 patients from group B required the introduction of parenteral nutrition. In this group of patients, the authors observed dysphagia, anorexia, and rapid weight loss soon after transplantation, as early as moment 2 of the evaluation.

We did not observe other infections, such as those caused by anaerobic organisms in our study probably due to preventive measures with oral fluconazole and nystatin, as well as the use of antiseptic mouthwash, which are a standard procedure in all patients undergoing HSCT.10,14,15

Undoubtedly, the most feared complication of bone marrow transplantation is death, that occurs in 15–20% of allogeneic transplantations and in 5% of autologous transplantations. Is this related to oral alterations? Death occurred in seven of the present patients, between moments 2 and 3 after transplantation. One of the deaths occurred in group B, from multiple-organ failure and veno-occlusive disease. In group A, six patients died. Of these, four died due to disease recurrence, one patient died due to pneumonia and respiratory failure, and one patient due to acute host-versus-graft disease and sepsis. In none of them were the causes associated with oral disease. Although mucositis is the main alteration responsible for the increase in clinical complications, especially infectious ones associated to conditioning toxicity, such lesions were not seen in these patients at the time of death, perhaps due to the dramatic moment experienced by patients and the medical staff.

ConclusionWe affirm that mucositis is the oral cavity alteration of greatest concern as a potential risk for complications in immunosuppressed patients. Other lesions, such as gingivitis and third-molar pericoronitis, considered as low-risk indicators in this study were also less relevant. This alterations became more evident when the mild, moderate and severe risk and toxicity scores were used to assess the clinical complications in immunossupressed individuals.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Barrach RH, de Souza MP, da Silva DP, Lopez PS, Montovani JC. Oral changes in individuals undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;81:141–7.