In developing countries, terrestrial transport accidents – TTA, especially those involving automobiles and motorcycles – are a major cause of facial trauma, surpassing urban violence.

ObjectiveThis cross-sectional census study attempted to determine facial trauma occurrence with terrestrial transport accidents etiology, involving cars, motorcycles, or accidents with pedestrians in the northeastern region of Brazil, and examine victims’ socio-demographic characteristics.

MethodsMorbidity data from forensic service reports of victims who sought care from January to December 2012 were analyzed.

ResultsAltogether, 2379 reports were evaluated, of which 673 were related to terrestrial transport accidents and 103 involved facial trauma. Three previously trained and calibrated researchers collected data using a specific form. Facial trauma occurrence rate was 15.3% (n=103). The most affected age group was 20–29 years (48.3%), and more men than women were affected (2.81:1). Motorcycles were involved in the majority of accidents resulting in facial trauma (66.3%).

ConclusionThe occurrence of facial trauma in terrestrial transport accident victims tends to affect a greater proportion of young and male subjects, and the most prevalent accidents involve motorcycles.

Nos países em desenvolvimento, os acidentes de transporte terrestre (ATTs) são uma das principais causas de trauma facial, superando os casos de violência urbana, especialmente aqueles envolvendo automóveis e motocicletas.

ObjetivoO objetivo deste estudo transversal censitário foi determinar a ocorrência de traumas faciais com etiologia de acidente de transporte terrestre (ATT): automóveis, motocicletas ou atropelamentos, em uma cidade do Nordeste do Brasil.

MétodoForam analisados os dados de morbidade em laudos de um serviço forense de vítimas que procuraram o serviço de janeiro a dezembro de 2010.

ResultadosAo todo, foram avaliados 2.379 laudos; 673 eram referentes a ATTs, e 103 apresentaram traumas faciais. A coleta de dados foi realizada por três pesquisadores previamente treinados e calibrados, sendo elaborado um formulário específico para coleta das informações contidas nos laudos. Destes, 15,3% (n=103) sofreram trauma facial. A faixa etária predominante para os eventos de trauma facial foi de 20-29 anos (48,3%), acometendo mais homens do que mulheres (2,81:1). A motocicleta foi o principal tipo de veículo com envolvimento de vítimas (66,3%).

ConclusõesA ocorrência de traumas faciais em vítimas de acidente de transporte terrestre tende a afetar, em maior proporção, indivíduos homens e jovens, com maior prevalência para os acidentes envolvendo motocicletas.

In developing countries, terrestrial transport accidents (TTAs), especially those involving automobiles and motorcycles, are one of the main causes of facial trauma, surpassing even cases of urban violence.1–4 Facial trauma prevalence has larger negative social consequences as it is related to lower productivity and higher loss of work time rates compared to other morbidities such as heart disease and cancer.5

Among the types of vehicles involved in accidents, motorcycles have caused a large number of traffic deaths, primarily because it is a means of transportation that does not ensure the driver's safety, leading to multiple traumas. Incorrect use of personal protective equipment, particularly helmets, can cause serious injuries to victims’ faces.5–7

Drug and alcohol use is related to TTA occurrence8,9; in addition, the number of vehicles in cities has been increasing, putting more individuals at risk.10,11 Studies aimed at identifying facial trauma highlight the need for improving public road safety policies, which in turn could reduce traffic-related morbidity and mortality.12,13

Facial injuries are considered a serious public health issue in both developed and developing countries. Thus, examining factors associated with facial injuries from TTAs can help determine prognosis, identify groups at risk, and establish measures to minimize economic, emotional, psychological and social impacts of these events.

Given the high prevalence of trauma resulting from traffic accidents, this study aimed to determine the socio-demographic characteristics and the occurrence rate of facial trauma with a TTA etiology involving cars, motorcycles, mopeds, and pedestrians admitted to a forensic unit in northeastern Brazil.

MethodsA cross-sectional census study was performed using 2379 reports of victims who sought the Department of Forensic Medicine and Dentistry's services, Campina Grande, PB, a city with approximately 687,545 inhabitants in northeastern Brazil, from January to December 2012. Among these, 673 reports had experienced TTAs. The 103 individuals who suffered facial injuries were included in the sample.

The reports were originally written by professionals who acted as medical and/or dentistry experts at the time of examination. The reports, noting the extent of damage caused by the trauma, were completed during the corpus delicti examination conducted independently. Legible reports of individuals who were alive at the time of examination were included. Illegible reports required a more thorough analysis by the expert physician or surgeon-dentist who was on duty at the time of data collection. Thus, 0.2% of all reports were excluded because of incomprehensible raw data.

The report is an official document used to apply for the Personal Injuries Caused by Motor Vehicles insurance. This is a compulsory annual contract between the state and insurance companies, paid annually by car owners when renewing their automobile license, with the main purpose of compensating traffic accident victims.

The data collection form gathered socio-demographic (age, sex, marital status, education and occupation), accident-related (accident type, day and time), and injury-related data (anatomical area: front, masseteric, mandibular, nasal, oral, orbital, zygomatic, and polytrauma).

Data were analyzed using SPSS, version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA); frequency distributions were used to characterize socio-demographic and TTA-related data for facial trauma victims. The association between independent variables and the occurrence of facial trauma was examined using Fisher's exact probability test and Pearson's chi-square test at 5% significance. Multivariate analysis was performed using Poisson regression.

This study was registered at the National System of Ethics on Research; it was submitted to and approved under Council of Alumni Association Executives n° 0652.0.133.000-11, and it was authorized by the director of the Forensic Unit responsible for the safekeeping of victims’ reports. The study followed the guidelines explained in the “STROBE Statement”.14

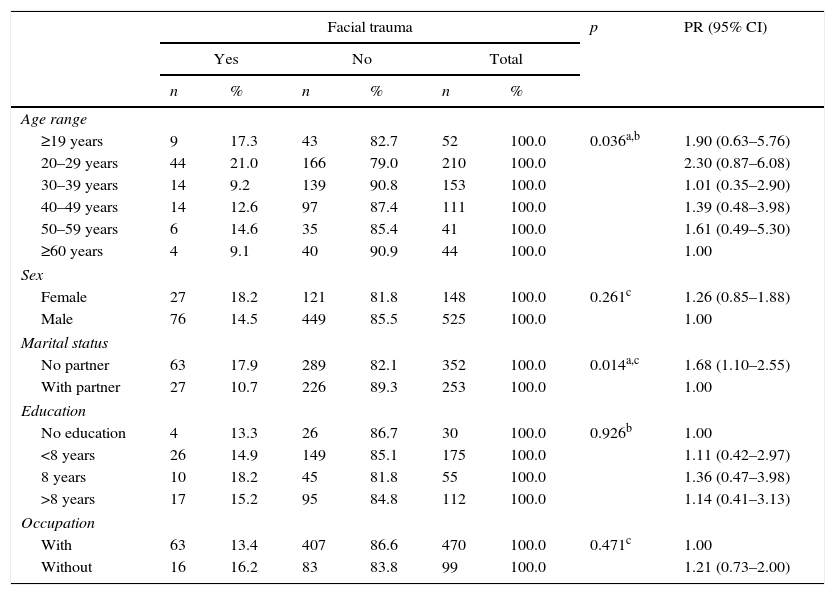

ResultsFacial injuries were observed in 103 cases (15.3%). Table 1 shows the socio-demographic data with bivariate analysis of facial trauma for TTA cases. The age group with the highest number of facial trauma events was 20–29 years (48.3%, n=44). Men were more likely to be involved, with a male–female ratio of 2.81:1. Most victims of facial trauma were unmarried (70%, n=63) and had less than 8 years of education. Age and marital status were associated with facial trauma in the bivariate analysis.

Bivariate analysis of the occurrence of facial trauma and socio-demographic characteristics of victims of terrestrial transport accidents.

| Facial trauma | p | PR (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Total | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Age range | ||||||||

| ≥19 years | 9 | 17.3 | 43 | 82.7 | 52 | 100.0 | 0.036a,b | 1.90 (0.63–5.76) |

| 20–29 years | 44 | 21.0 | 166 | 79.0 | 210 | 100.0 | 2.30 (0.87–6.08) | |

| 30–39 years | 14 | 9.2 | 139 | 90.8 | 153 | 100.0 | 1.01 (0.35–2.90) | |

| 40–49 years | 14 | 12.6 | 97 | 87.4 | 111 | 100.0 | 1.39 (0.48–3.98) | |

| 50–59 years | 6 | 14.6 | 35 | 85.4 | 41 | 100.0 | 1.61 (0.49–5.30) | |

| ≥60 years | 4 | 9.1 | 40 | 90.9 | 44 | 100.0 | 1.00 | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 27 | 18.2 | 121 | 81.8 | 148 | 100.0 | 0.261c | 1.26 (0.85–1.88) |

| Male | 76 | 14.5 | 449 | 85.5 | 525 | 100.0 | 1.00 | |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| No partner | 63 | 17.9 | 289 | 82.1 | 352 | 100.0 | 0.014a,c | 1.68 (1.10–2.55) |

| With partner | 27 | 10.7 | 226 | 89.3 | 253 | 100.0 | 1.00 | |

| Education | ||||||||

| No education | 4 | 13.3 | 26 | 86.7 | 30 | 100.0 | 0.926b | 1.00 |

| <8 years | 26 | 14.9 | 149 | 85.1 | 175 | 100.0 | 1.11 (0.42–2.97) | |

| 8 years | 10 | 18.2 | 45 | 81.8 | 55 | 100.0 | 1.36 (0.47–3.98) | |

| >8 years | 17 | 15.2 | 95 | 84.8 | 112 | 100.0 | 1.14 (0.41–3.13) | |

| Occupation | ||||||||

| With | 63 | 13.4 | 407 | 86.6 | 470 | 100.0 | 0.471c | 1.00 |

| Without | 16 | 16.2 | 83 | 83.8 | 99 | 100.0 | 1.21 (0.73–2.00) | |

PR, prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval.

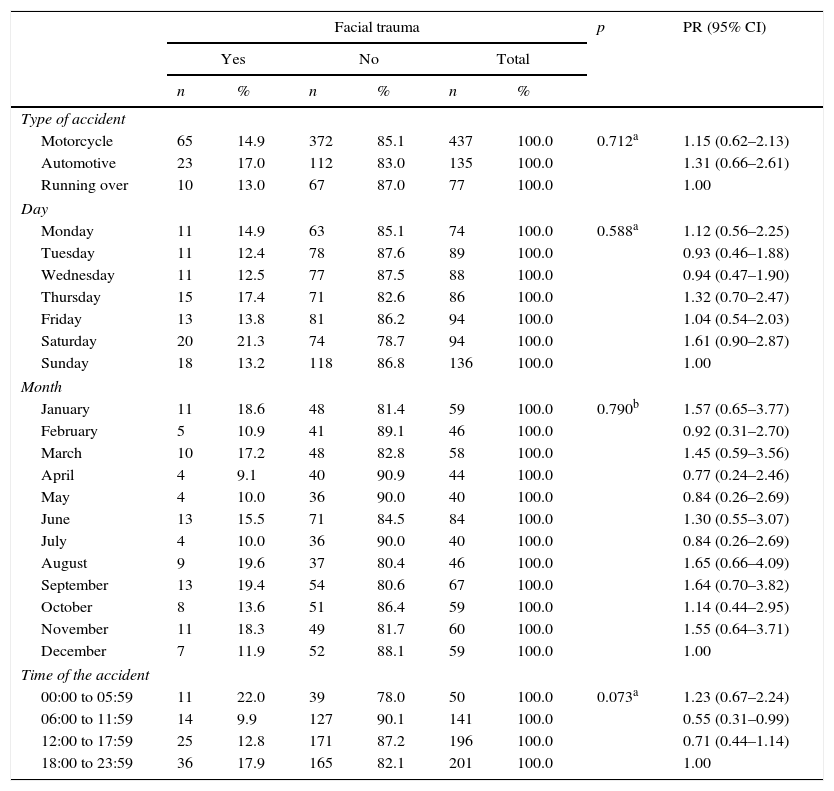

The majority of TTA cases with facial trauma victims involved motorcycles (66.3%, n=65). Accidents occurred most frequently on Saturdays (20.2%, n=20), followed by Sundays (18.2%, n=18); regarding month, June and September had the highest frequency (13.1% each, n=13). Most accidents occurred at night, between 18:00 to 23:59 (41.9%, n=36). The bivariate analysis of facial trauma occurrence and TTA-related variables indicated no significant statistical association (Table 2).

Bivariate analysis between facial trauma and data related to the occurrence of terrestrial transport accidents.

| Facial trauma | p | PR (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Total | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Type of accident | ||||||||

| Motorcycle | 65 | 14.9 | 372 | 85.1 | 437 | 100.0 | 0.712a | 1.15 (0.62–2.13) |

| Automotive | 23 | 17.0 | 112 | 83.0 | 135 | 100.0 | 1.31 (0.66–2.61) | |

| Running over | 10 | 13.0 | 67 | 87.0 | 77 | 100.0 | 1.00 | |

| Day | ||||||||

| Monday | 11 | 14.9 | 63 | 85.1 | 74 | 100.0 | 0.588a | 1.12 (0.56–2.25) |

| Tuesday | 11 | 12.4 | 78 | 87.6 | 89 | 100.0 | 0.93 (0.46–1.88) | |

| Wednesday | 11 | 12.5 | 77 | 87.5 | 88 | 100.0 | 0.94 (0.47–1.90) | |

| Thursday | 15 | 17.4 | 71 | 82.6 | 86 | 100.0 | 1.32 (0.70–2.47) | |

| Friday | 13 | 13.8 | 81 | 86.2 | 94 | 100.0 | 1.04 (0.54–2.03) | |

| Saturday | 20 | 21.3 | 74 | 78.7 | 94 | 100.0 | 1.61 (0.90–2.87) | |

| Sunday | 18 | 13.2 | 118 | 86.8 | 136 | 100.0 | 1.00 | |

| Month | ||||||||

| January | 11 | 18.6 | 48 | 81.4 | 59 | 100.0 | 0.790b | 1.57 (0.65–3.77) |

| February | 5 | 10.9 | 41 | 89.1 | 46 | 100.0 | 0.92 (0.31–2.70) | |

| March | 10 | 17.2 | 48 | 82.8 | 58 | 100.0 | 1.45 (0.59–3.56) | |

| April | 4 | 9.1 | 40 | 90.9 | 44 | 100.0 | 0.77 (0.24–2.46) | |

| May | 4 | 10.0 | 36 | 90.0 | 40 | 100.0 | 0.84 (0.26–2.69) | |

| June | 13 | 15.5 | 71 | 84.5 | 84 | 100.0 | 1.30 (0.55–3.07) | |

| July | 4 | 10.0 | 36 | 90.0 | 40 | 100.0 | 0.84 (0.26–2.69) | |

| August | 9 | 19.6 | 37 | 80.4 | 46 | 100.0 | 1.65 (0.66–4.09) | |

| September | 13 | 19.4 | 54 | 80.6 | 67 | 100.0 | 1.64 (0.70–3.82) | |

| October | 8 | 13.6 | 51 | 86.4 | 59 | 100.0 | 1.14 (0.44–2.95) | |

| November | 11 | 18.3 | 49 | 81.7 | 60 | 100.0 | 1.55 (0.64–3.71) | |

| December | 7 | 11.9 | 52 | 88.1 | 59 | 100.0 | 1.00 | |

| Time of the accident | ||||||||

| 00:00 to 05:59 | 11 | 22.0 | 39 | 78.0 | 50 | 100.0 | 0.073a | 1.23 (0.67–2.24) |

| 06:00 to 11:59 | 14 | 9.9 | 127 | 90.1 | 141 | 100.0 | 0.55 (0.31–0.99) | |

| 12:00 to 17:59 | 25 | 12.8 | 171 | 87.2 | 196 | 100.0 | 0.71 (0.44–1.14) | |

| 18:00 to 23:59 | 36 | 17.9 | 165 | 82.1 | 201 | 100.0 | 1.00 | |

PR, Prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval.

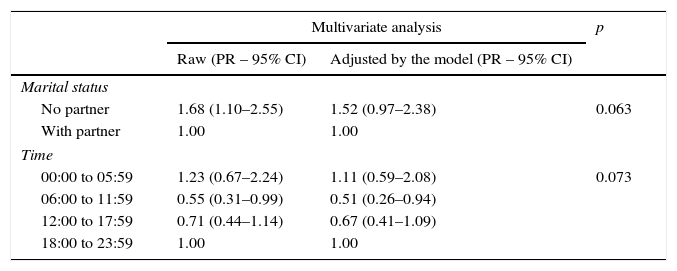

Multivariate analysis from the Poisson regression showed no significant association for variables included in the model. Although age was significant in the bivariate analysis, it could not be adjusted in the multivariate model due to the large number of categories (Table 3).

Poisson multivariate regression for analysis of percentage of facial injury based on independent variables included in the model.

| Multivariate analysis | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw (PR – 95% CI) | Adjusted by the model (PR – 95% CI) | ||

| Marital status | |||

| No partner | 1.68 (1.10–2.55) | 1.52 (0.97–2.38) | 0.063 |

| With partner | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Time | |||

| 00:00 to 05:59 | 1.23 (0.67–2.24) | 1.11 (0.59–2.08) | 0.073 |

| 06:00 to 11:59 | 0.55 (0.31–0.99) | 0.51 (0.26–0.94) | |

| 12:00 to 17:59 | 0.71 (0.44–1.14) | 0.67 (0.41–1.09) | |

| 18:00 to 23:59 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

PR, prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Font: NUMOL: 2012.

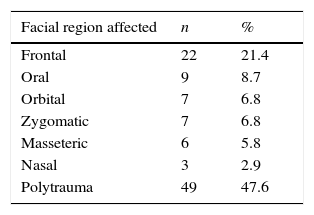

With regard to the anatomical location of facial trauma, there were more multiple traumas (47.6%); however, in isolation, the frontal region was most affected (21.4%) (Table 4).

DiscussionStudies in forensic medicine departments are rare since most deal with mortality and morbidity data obtained from hospitals. Thus, the present study provides differing information.

The victims considered highlight the differences which may occur when we observe data for treatment at forensic medical and dental services, in which the individual claims his/her citizen's rights, or in health services, in which the aim is to remedy injury to health.

This study suggests that facial trauma cases – registered in a forensic unit – are not rare and their occurrence is highest among young people, especially those between 20 and 29 years. A similar study conducted in Portugal found a 11.6% prevalence of facial trauma in a forensic institute, a rate consistent with the 15.3% reported in the present study.15 Young people are more likely to be in accidents that result in facial trauma.1,3,16–19 They participate more intensely in social life compared to children, adults, and elderly individuals, and are therefore more likely to face TTAs involving fractures and facial trauma.2 Additionally, young people present traffic behaviors that increase the risk of accidents, such as immaturity, inexperience and recklessness.20

Other risk factors for facial trauma that young people are more likely to be exposed to include contact sports, alcohol and recreational drugs.20 A study conducted in Brazil with victims of facial trauma determined that those between 21 and 30 years are at risk for facial trauma.6

Regarding gender, men were more likely to be TTA victims, consistent with previous studies.3,4,21 In Brazil,1–4 Africa21 and the United Arab Emirates,22 the male–female ratio of facial trauma cases tends to be higher than in more developed countries like Germany,17 the United States18 and Switzerland.23 This is because in developing countries, men, more than women, are involved in active economic life, which exposes them to risk factors such as unsafe traffic behavior.6,21

The bivariate analysis in the present study revealed that the occurrence of facial trauma was associated with marital status; a significantly large number of unmarried individuals experienced facial trauma. However, this association was not supported by the multivariate analysis. Other variables such as education and employment were not significantly associated with facial trauma in any of the analyses. Despite the absence of a statistical association, unmarried individuals were most likely to be involved in violent situations, and most had a low level of education. This low educational level may be a reflection of the socioeconomic conditions of the region under study, where access to education was delayed due to educational policy failures and inefficient health policy implementation.24,25

The majority of accidents recorded involved motorcycles, followed by automobiles. The motorcycle is the most unsafe vehicle, as the rider's body is exposed and unprotected, making him/her extremely vulnerable to accidents that could result in morbidity or death.5 In Brazil, the number of fatal motorcycle accidents increased by 754% within a decade and continues to increase every year.26

This increased morbidity and mortality in traffic is explained by reckless driving, mainly resulting from alcohol use.9,27 In addition, with the increased number of motorcycles in Brazil, the likelihood of accidents has also increased. In 1998, the number of the motorcycles in Brazil was 2,542,732; this increased to 9,410,110 in 2007, corresponding to approximately 4970 motorcycles per 10,000 inhabitants.26

In this study, accidents occurred more frequently on Saturdays and Sundays, which are weekend days when people are more likely to consume alcohol. This may explain the high number of alcohol-related accidents and consequently, the occurrence of facial trauma. June and September were the months with the most number of facial trauma cases. The city hosts a popular event every June, resulting in an increase in the number of people in the city and thus increasing the likelihood of TTA occurrences.

TTAs resulting in facial trauma mainly occurred at night between 18:00 to 23:59. This may be a reflection of the greater number of social activities involving alcohol consumption that take place during this time, resulting in a greater number of accidents.

Regarding the anatomical location of facial trauma, polytrauma was most common. The biomechanics of collisions affects trauma profiles; falls at high speed involving motorcyclists often affect the cervical spine and related areas.28,29 It is therefore unsurprising that several areas were affected. In isolation, the major affected areas were the frontal and oral regions. Typically, trauma location depends on the lesion severity.1 In accidents involving fractures, the mandible region is more likely to be affected.18,22,30 In this study, all cases of mandibular fractures were involved in other regions and were included as polytrauma. Soft tissue injuries affect areas around the jaw, such as oral, nasal, and zygomatic regions.6 The occurrence of facial trauma can complicate individuals’ health since it can cause deformities in face physiognomy and emotional sequelae.

A limitation of this cross-sectional study is that it could not establish causal relationships. Because of this region's socioeconomic background, there is no integrated system of epidemiological surveillance between stations of police, forensic services, and emergency units at hospitals. Thus, the prevalence of facial trauma, although considered high, may be an underestimation since several individuals may have been directly forwarded to receive hospital care, bypassing forensic services.

Currently, there is limited information on the prevalence and factors associated with morbidity among victims admitted to forensic services. Most scientific TTA-related studies were conducted within short time periods. Moreover, they examined cases of individuals admitted to surgery and traumatology departments.

Future research that aims at identifying differences between cases of facial trauma admitted to emergency and forensic services is necessary. In addition, although it was not possible to estimate the impact and consequences of these accidents (as the reports did not include this information), it is essential to carry out surveys to accurately assess the effect of morbidity on victims’ quality of life.

This study examined the characteristics of TTAs and their victims, focusing on facial trauma distribution patterns among victims admitted to a forensic service. Moreover, it is a pioneering research in this geographical region.31

These results could be used to help authorities create an integrated network for epidemiological monitoring and for planning prevention, rehabilitation, and social support programs for victims of TTA-related trauma.

ConclusionsThis study emphasizes that Brazilian authorities need to pay greater attention to road safety. Regulatory laws may reduce the number of TTAs and the resulting morbidity and mortality.

The occurrence of facial traumas in TTA victims is not rare; it is observed more frequently in young individuals and men, and is most likely to involve motorcycles.

FundingThis study was funded by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), a Brazilian science promotion agency, and supported by Coordenação Nacional de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: d’Avila S, Barbosa KGN, Bernardino IM, da Nóbrega LM, Bento PM, e Ferreira EF. Facial trauma among victims of terrestrial transport accidents. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;82:314–20.