A considerable high number of SNHL patients also suffer from dizziness and related vestibular symptoms.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the association of vestibular dysfunction and sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) in adult patients.

MethodsProspective, double-blinded, controlled studies composed by 63 adult patients without any vestibular symptoms or diagnosed vestibular diseases. Audiological status was measured with pure tone audiometry and the vestibular system was tested with vestibular evoked myogenic potential (VEMP). Patients were divided into two groups: a study group (patients with SNHL) and a control group (patients without SNHL). VEMP results of the groups were calculated and compared.

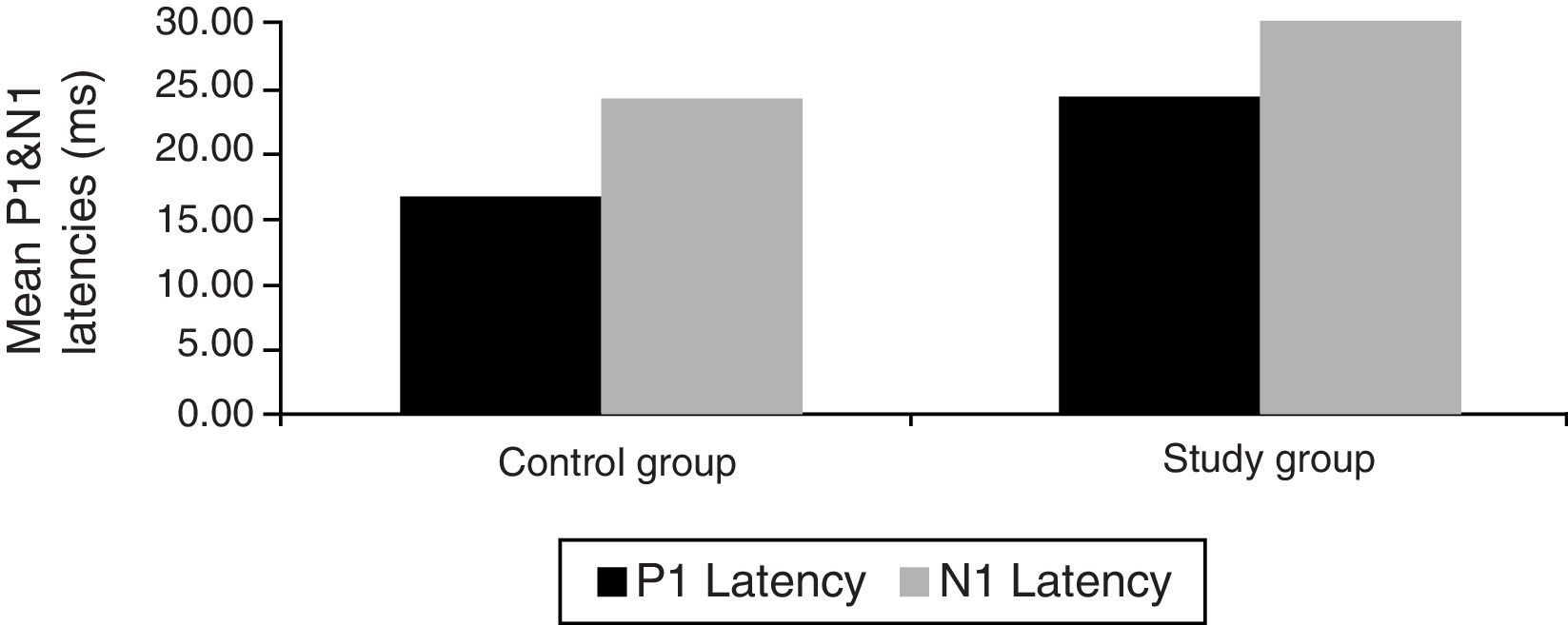

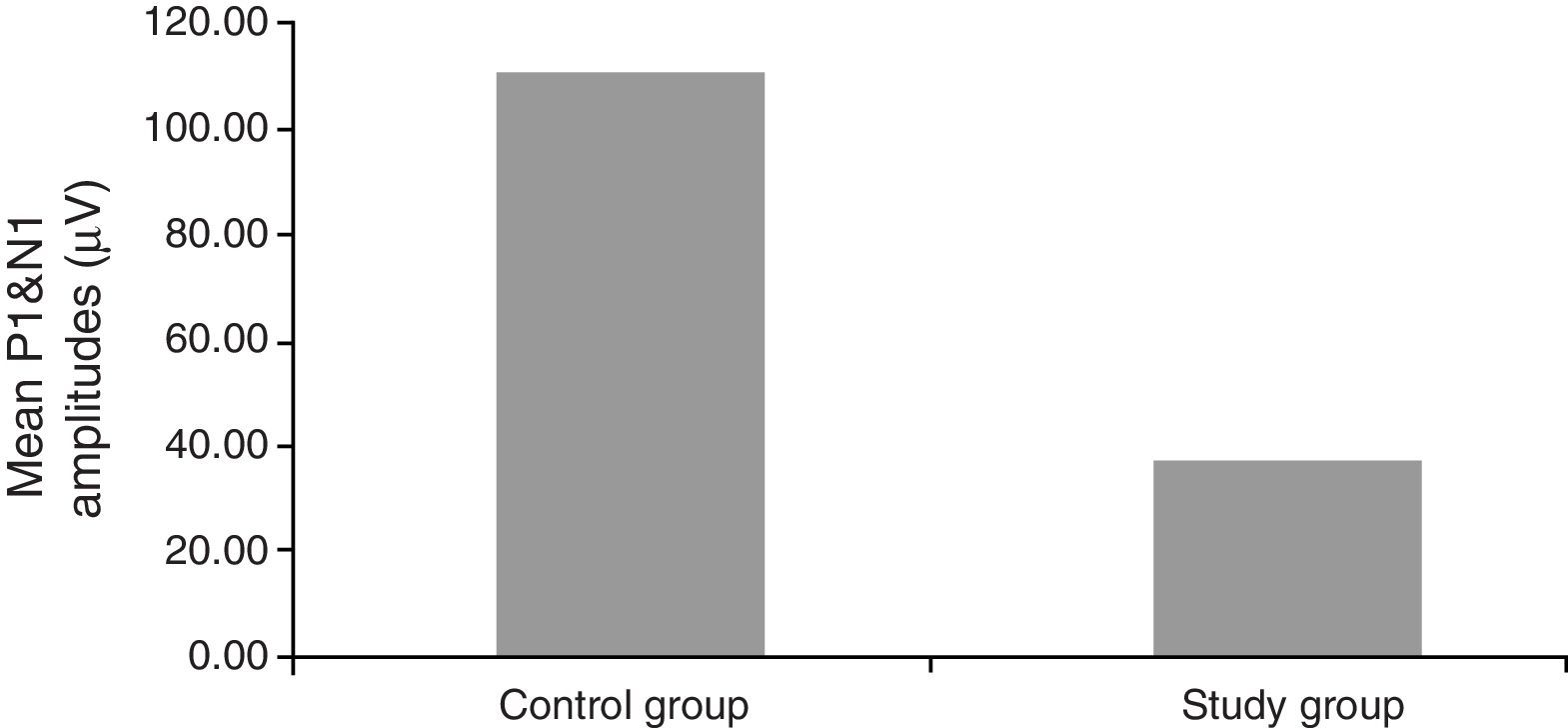

ResultsMean P1 (23.54) and N1 (30.70) latencies were prolonged in the study group (p<0.001) and the amplitudes of the study group were significantly reduced (p<0.001). Both parameters of the VEMP test were abnormal in the study group when compared to the control group.

ConclusionsThese findings suggest that age-related SNHL may be accompanied by vestibular weakness without any possible predisposing factors for vestibulopathy.

Um número considerável de pacientes com PANS também sofre de tonturas e sintomas vestibulares relacionados.

ObjetivoAvaliar a associação entre disfunção vestibular e perda auditiva neurossensorial (PANS) em pacientes adultos.

MétodoEstudo prospectivo, duplo-cego e controlado com 63 pacientes adultos, sem quaisquer sintomas vestibulares ou doença vestibular diagnosticada. A audição foi avaliada por meio de audiometria tonal e o sistema vestibular, com potenciais evocados miogênicos vestibulares (PEMV). Os pacientes foram divididos em dois grupos: grupo de estudo (pacientes com PANS) e grupo de controle (pacientes sem PANS). Os resultados dos PEMV dos grupos foram calculados e comparados.

ResultadosAs latências médias de P1 (23,54) e N1 (30,70) encontravam-se prolongadas no grupo de estudo (p<0,001), e as amplitudes no grupo de estudo estavam significantemente reduzidas (p<0,001). Ambos os parâmetros do teste de PEMV foram anormais no grupo de estudo quando comparados aos do grupo controle.

ConclusõesNossas achados sugerem que a PANS relacionada à idade pode ser acompanhada por hipofunção vestibular, mesmo na ausência de possíveis fatores predisponentes para vestibulopatia.

Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) is the most common type of sensorial deficiency, affecting over 360 million people across the globe, and it is considered a public health problem regardless of the etiology.1 A considerable high number of SNHL patients also suffer from dizziness and related vestibular symptoms. A relationship is therefore highly possible between SNHL and vestibular dysfunction, in the absence of evidences of any inner ear or systemic diseases that could cause vestibulopathy. Many patients present to otolaryngology clinics with dizziness and hearing loss problems with no obvious pathology and are diagnosed with presbyacusis or age-related vestibulopathy.

This study aims to evaluate the relationship between the substructures of the vestibular system and the hearing organs with the same embryological origin. Pathologies affecting one subside of the inner ear may therefore cause a dysfunction in the parts with the same embryological origin. From this point forth we investigated the saccule as a part of the vestibular system using the Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials (VEMP) as it is one of the most accurate and practical ways to assess the integrity and function of the saccule and inferior vestibular nerve. The principle of this diagnostic toolshed results from the selective activation of vestibular nerve afferents innervating the saccule. Cervical VEMP responses are recorded with Electromyography (EMG) of the Sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle after the onset of a click stimulus to the external ear canal.2 It is a biphasic response that evaluates the sacculocollic reflex.

The number of relevant studies is limited as case reports constitute the vast majority of these papers. This lack of data motivated us to search and seek for more knowledge about these indistinct patients. In this study, we investigated the relationship between SNHL and vestibular dysfunction in adults based on the hypothesis that the malfunction in one subside, may affect the parts of vestibular and hearing system with the same embryological origin.

MethodsA prospective, double-blinded, controlled study was conducted on adult patients. The study group consisted of patients admitted in our institute with a hearing loss complaint, diagnosed with bilateral moderate to severe SNHL. A control group with similar demographic features was formed by healthy individuals without hearing loss. Patients with mixed types of hearing loss, external ear canal pathologies, perforated tympanic membrane, abnormal middle ear functions, any kind of vascular or diagnosed neurological diseases, confirmed peripheral vestibular diseases, or a history of otologic or lateral skull base surgery were excluded.

Pure Tone Audiometry (PTA) was evaluated using an AD629 Interacoustics® (Denmark, 2012) device in a sound proof room to screen the hearing status of each participant for the frequencies 250–8000Hz. A pure tone threshold in the range of 41–60dB HL was considered as moderate and 61–80dB HL as severe SNHL.3 Middle ear functions were evaluated by tympanometry and acoustic reflex testing.

Saccular function was tested by VEMP. Brief broadband clicks of 0.1msn were used as stimulant and a surface EMG of the SCM muscle was recorded. The non-inverting electrode was placed on the upper third of the muscle and the inverting electrode was placed over the SCM tendon above the clavicula. The patients were positioned upright and instructed to turn their heads toward the contralateral side of the tested ear. The state of contraction of SCM was equalized before the stimulation by means of a preload control system. The EMG response of the muscle was recorded as biphasic wave forms according to latencies (P1 and N1) at a stimulus level of 95dB HL, 500Hz tone burst with 4msn rise/fall time and 2msn plateau with a repetition rate of 5.5s. The latencies and amplitudes of VEMP in each ear were calculated for each group and compared. The auditory and vestibular testing were performed double-blinded by separate researchers. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects, and this study was approved by the institutional Review Board (IRB 682).

Statistical methodsDescriptive statistics were obtained from each group; mean values, standard deviations, and medians were calculated. Fisher's exact test and the chi-squared test were used to compare VEMP results between groups. SPSS 15.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, United States) was used for all statistical analyses, and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

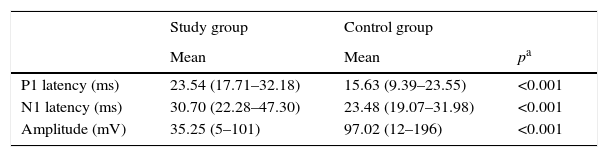

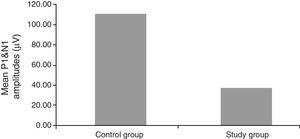

ResultsIn total, 63 patients with a mean age of 65.1 years (min–max 55–82 years) were included in the study. The mean age in the study group was 67.2 years, while it was 64.2 in the control group (p>0.05). There were 39 female and 24 male patients (p>0.05), with no preponderance in terms of gender and age between the groups. The study and control groups consisted of 31 and 32 patients, respectively. Mean PTA value was 20.71dB (min–max 10–25) in the control group and 63.53dB (min–max 50–83) in the study group (p<0.05). Mean P1 and N1 latencies and amplitudes of the groups are summarized in Table 1. Both P1 and N1 latencies were significantly prolonged in the study group when compared to the control group (p<0.001; Fig. 1). The amplitudes were also significantly reduced in the study group (p<0.001; Fig. 2).

Mean values of latencies and amplitudes in study and control groups.

| Study group | Control group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | pa | |

| P1 latency (ms) | 23.54 (17.71–32.18) | 15.63 (9.39–23.55) | <0.001 |

| N1 latency (ms) | 30.70 (22.28–47.30) | 23.48 (19.07–31.98) | <0.001 |

| Amplitude (mV) | 35.25 (5–101) | 97.02 (12–196) | <0.001 |

The relationship between SNHL and the vestibular system is complex and not clearly understood. The mechanism of the interaction between the auditory and vestibular systems in patients with SNHL remains to be discovered. Previous studies have focused on the possibility of a relation between noise-induced hearing loss and impaired vestibular functions.4 In a study among patients diagnosed with noise-induced hearing loss, 50% of the subjects had abnormal VEMP results.5 In addition, the anatomical proximity of the saccule to the footplate of the stapes may have a potential role in vestibular dysfunction, particularly in patients with a history of chronic noise exposure. In another study, Singh et al.6 reported a possible relationship, based on the significant reduction observed in the amplitudes of VEMP results in children with severe to profound SNHL.

From an embryological point of view, the saccule and cochlea develop from the same origin in the membranous labyrinth, which is innervated by the inferior portion of the vestibular nerve. Furthermore, the saccule acts as an acoustic-sensitive organ in lower species;7,8 therefore, as a vestibular-sensitive organ, it can be considered as a late development in humans.9,10

Many patients with different types of presbycusis suffer from vestibular dysfunction. Whether this vestibulopathy is due to age-related changes in the central nervous system or whether an association exists between SNHL and vestibular disease is unclear. Thus, in the present study, the groups were formed homogenously, thereby eliminating any possible factors that could cause vestibular dysfunction. The prolonged P1 and N1 latency periods and the reduction of the amplitudes observed in the study group suggested a peripheral vestibular deficit in the patients with SNHL. This research was based on the hypothesis that pathologies affecting one subside of the inner ear may cause a dysfunction in the parts with the same embryological origin. Our findings suggest that SNHL may be accompanied by vestibular weakness, without any possible predisposing factors for vestibulopathies.

The weak part of this study is the lack of data concerning ocular VEMP and canal reflectance which may be an expression of the differences in the global inner ear impairment that occur from aging. The correlation between hearing loss and vestibular dysfunction may depend on multiple variables. Thus further studies with larger number of patients and supported with different types of vestibular tests to evaluate the integrity of vestibular system will expand awareness for this issue.

A vast amount of patients with SNHL, regardless the etiology, have some degree of vestibular dysfunction. Apart from their diagnosis with peripheral vestibular diseases, most of these patients visit different departments including cardiology, internal medicine, geriatrics, or physical therapy and rehabilitation while seeking for the diagnosis of their pathology. Many otolaryngologists also examine these patients in their daily routine. In the light of our results, we can conclude that detailed information about the status of the inferior portion of the vestibular system, in conjunction with auditory functions, may guide the clinician in the right direction for assessment of these patients.

ConclusionThe findings suggest that age-related SNHL may be accompanied by vestibular weakness without any possible predisposing factors for vestibulopathy.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Kurtaran H, Acar B, Ocak E, Mirici E. The relationship between senile hearing loss and vestibular activity. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;82:650–3.