Acute longus colli tendinitis is caused by calcium hydroxyapatite deposition in the tendon of the longus colli muscle with subsequent inflammation. The calcifications are commonly located at the superior oblique portion at the level of the C1–C2 vertebrae. The typical clinical presentation consists of acute neck pain, odynophagia, and painful limitation of neck range of motion.

ObjectivesWe will describe this disease with three that cases presented to our institution and compare the findings on imaging studies.

MethodsWe retrospectively reviewed the clinical data, radiological features, and laboratory reports of three patients diagnosed with acute longus colli tendinitis. Computed tomography and plain radiographs were reviewed and compared by a single radiologist. A contemporary review of the literature was conducted using PubMed (Medline), Embase, and Cochrane library databases.

ResultsComputed tomography showed greater sensitivity for the detection of the pathognomonic calcification than plain radiographs and facilitated the exclusion of other more severe conditions by following a systematic interpretation composed of five key elements. Plain radiographs showed non-specific signs of prevertebral soft tissue swelling and a decreased cervical lordotic curve. However, no calcification was identified on plain radiographs. The literature review revealed 153 articles containing 372 cases. Surgical or invasive procedures were mentioned in 13.7% of publications and were performed in 28 patients.

ConclusionAcute longus colli tendinitis can mimic the clinical presentation of more severe conditions that the otolaryngologist may be required to evaluate, such as infectious, traumatic, and neoplastic diseases. Knowledge of this entity, with its pathognomonic imaging findings, can prevent misdirected medical therapy and unnecessary invasive procedures.

Acute longus colli tendinitis (ALT) is an uncommon and underrecognized cause of atraumatic neck pain. The clinical presentation mimics more severe conditions of the prevertebral cervical region that the otolaryngologist may be required to evaluate, such as infectious, traumatic, and neoplastic diseases. However, to date it received little attention in the otolaryngology literature. Knowledge of this entity by otolaryngologists with its pathognomonic imaging findings can prevent misdirected medical therapy, unnecessary invasive procedures, patient anxiety, and delays in hospital discharge. We will describe this disease through three cases presented to our institution and review the relevant literature.

MethodsA computerized search of the medical charts of all the patients admitted to Emek Medical Center in Israel from inception to December 2020 identified three patients diagnosed with ALT between March 2018 and March 2019. An approved waiver was obtained from the institutional review board committee. A retrospective review of the medical chart included patients’ demographics, past medical history, clinical evaluation, and laboratory test results. All plain radiographs and computed tomography (CT) scans were extracted and inspected by a single radiologist, experienced in that field.

A contemporary review of the literature was conducted on August 2020 using PubMed (Medline), Embase, and Cochrane library databases using the following algorithm: “tendinopathy” (MESH term) or “tendinitis” or “tendonitis” combined with the Boolean operator “AND” to include the terms “longus colli” or “retropharyngeal” or “prevertebral”. A search with similar terms was conducted using the Cochrane Library and Embase database. Relevant articles were retrieved, and their references searched for further publications. Publications in languages other than English or publications without clinical data were excluded.

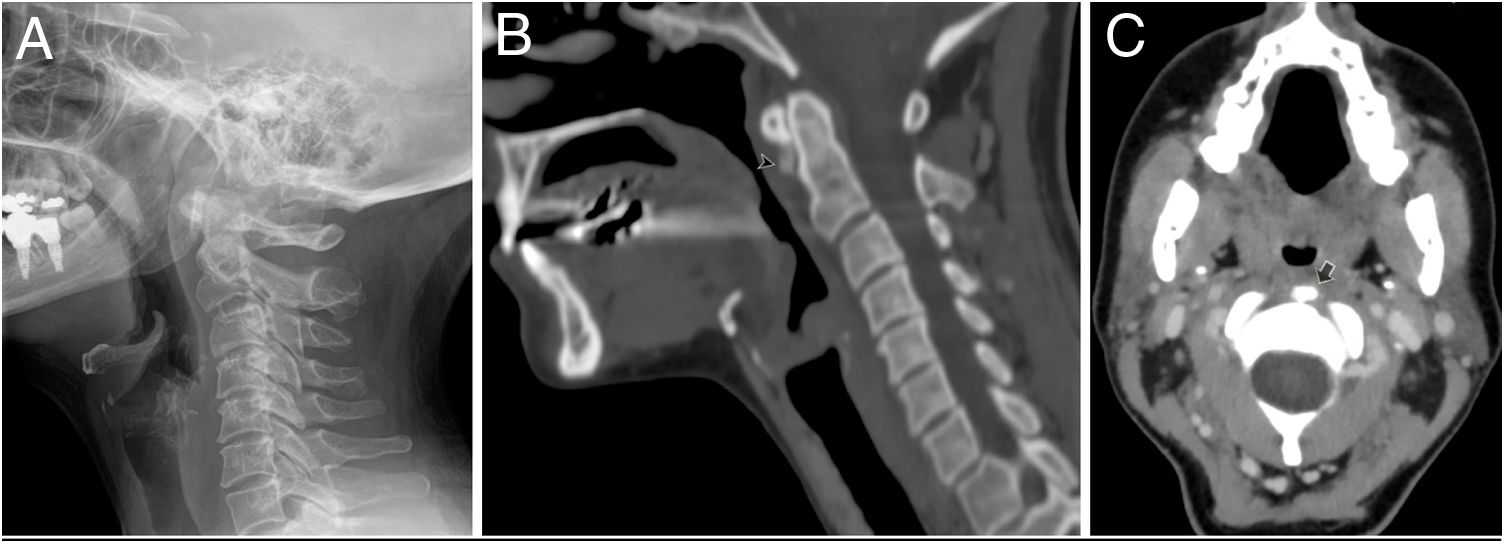

Case presentationCase oneA 48-year-old woman presented with a single day history of neck pain exacerbated with neck movement in every direction, limited neck range of movement, sore throat and odynophagia. The ENT (ear, nose, throat) examination, including fiberoptic laryngoscopy, revealed no abnormal findings. The patient had a limited range of motion (ROM) of the neck in all directions, with tenderness over her cervical spine and paravertebral area. The neurological examination was normal. She had an increased WBC count and mild elevation of the CRP level. Lateral neck radiograph showed prevertebral soft tissue swelling and a decreased cervical lordotic curve, but did not demonstrate calcifications (Fig. 1A). A CT scan showed prevertebral soft tissue swelling and effusion without wall enhancement, a decreased cervical lordotic curve, and the pathognomonic calcifications at the C1–C2 vertebrae level (Figs. 1B and C). She was diagnosed with ALT and discharged from the emergency ward with a regimen of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for 10 days. A followup exam 4 days later was normal with complete resolution of symptoms.

A 48-year-old woman with acute longus coli tendinitis. A, Plain radiograph showing thickness of prevertebral soft tissues and decreased cervical lordotic curve. B, Sagittal view of a computed tomography scan of the same patient showing the same findings and the typical amorphous calcifications (black arrowhead) at the level of the C1–C2 vertebrae, not visible on the plain radiograph. C, Axial view at the level of C2 vertebrae demonstrating the amorphous calcifications (black arrow) and increased thickness of prevertebral soft tissues.

A 52 year-old man presented with a 3 day history of neck pain exacerbated with neck extension, limited neck range of movement, sore throat and odynophagia. He had a history of dyslipidemia. The ENT examination, including fiberoptic laryngoscopy, revealed no abnormal findings. The patient had a limited ROM in neck extension, with tenderness over his cervical spine and paravertebral area. The neurological examination was normal. He showed an increased WBC count and elevated CRP levels. A lateral neck radiograph showed prevertebral soft tissue swelling and decreased cervical lordotic curve, but did not demonstrate calcifications. A CT scan showed prevertebral soft tissue swelling and effusion without wall enhancement, decreased cervical lordotic curve, and the pathognomonic calcifications at the C1–C2 vertebrae level. He was diagnosed with ALT and discharged from the emergency ward with a regimen of NSAIDs for 10 days. The followup exam was positive for cervical spine tenderness without any neck limitation or neurological sign. Due to pain with neck extension, he was treated with NSAIDs for another 10 days. Due to the prolonged duration of symptoms, he was sent for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which was normal. Complete resolution of symptoms occurred after 64 days.

Case threeA 31 year-old man had a 2 week history of neck pain exacerbated with neck extension, limited neck range of movement, sore throat, and odynophagia. The ENT examination, including indirect laryngoscopy, revealed no abnormal findings. The patient had a limited ROM in neck extension, without tenderness over his cervical spine. The neurological examination was normal. The white blood cell (WBC) count was within normal range. The C-reactive protein (CRP) level was elevated. A contrast-enhanced CT demonstrated calcification at the level of the C1–C2 vertebrae, retropharyngeal soft tissue swelling and effusion without wall enhancement. The cervical lordotic curve was normal. Due to the initial radiologic impression of a retropharyngeal abscess, he was hospitalized for 3 days and received intravenous antibiotics until a revision of the CT was made. He was then diagnosed with ALT and was discharged with a regimen of NSAIDs for 7 days. The patient lost to followup and then was interviewed by phone 2.5 years later. He recalled having been treated for one week and remained asymptomatic since.

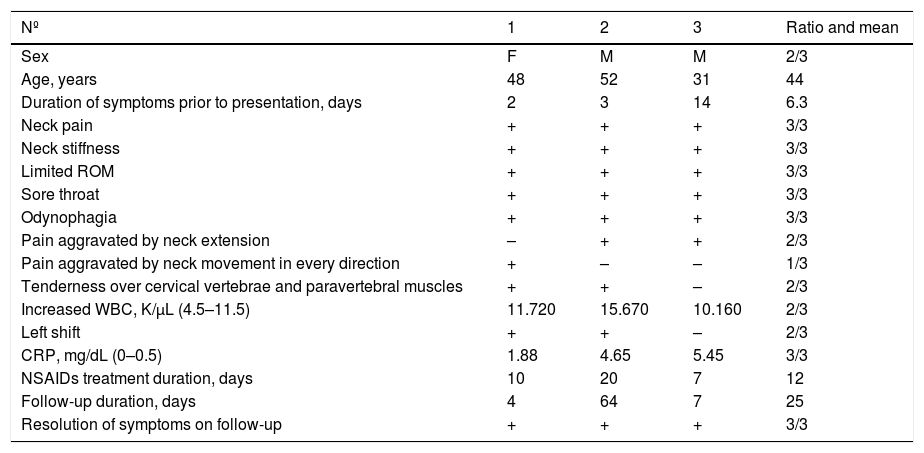

ResultsTwo males and one female presented with an average of 6.3 days history of neck pain, limited neck ROM, sore throat and odynophagia (Table 1). No patient reported dysphagia or decreased appetite. There was no dyspnea or hoarseness. None of the patients had a past event of acute neck pain or previous trauma. No patient had a fever. The physical exam was normal except for tenderness over the cervical spine and paravertebral area and limited ROM, more prominent on neck extension (2/3). Laboratory evaluation demonstrated elevated WBC count with left shift (2/3) and increased CRP level (3/3).

Summary of clinical findings.

| Nº | 1 | 2 | 3 | Ratio and mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | F | M | M | 2/3 |

| Age, years | 48 | 52 | 31 | 44 |

| Duration of symptoms prior to presentation, days | 2 | 3 | 14 | 6.3 |

| Neck pain | + | + | + | 3/3 |

| Neck stiffness | + | + | + | 3/3 |

| Limited ROM | + | + | + | 3/3 |

| Sore throat | + | + | + | 3/3 |

| Odynophagia | + | + | + | 3/3 |

| Pain aggravated by neck extension | – | + | + | 2/3 |

| Pain aggravated by neck movement in every direction | + | – | – | 1/3 |

| Tenderness over cervical vertebrae and paravertebral muscles | + | + | – | 2/3 |

| Increased WBC, K/µL (4.5–11.5) | 11.720 | 15.670 | 10.160 | 2/3 |

| Left shift | + | + | – | 2/3 |

| CRP, mg/dL (0–0.5) | 1.88 | 4.65 | 5.45 | 3/3 |

| NSAIDs treatment duration, days | 10 | 20 | 7 | 12 |

| Follow-up duration, days | 4 | 64 | 7 | 25 |

| Resolution of symptoms on follow-up | + | + | + | 3/3 |

M, Male; F, Female; WBC, White blood cell count; CRP, C-reactive protein; NSAIDs, Nonsteroidal anti-Inflammatory drugs; LTFU, Lost to follow-up; laboratory normal values are shown in parentheses.

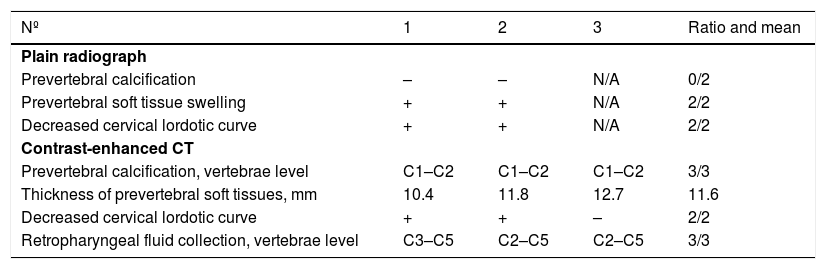

Both lateral neck radiographs did not show the typical calcification at the C1–C2 level, demonstrated later by CT due to its increased sensitivity (Table 2). All CT scans showed the pathognomonic calcifications at the C1–C2 levels, prevertebral soft tissue swelling and effusion without wall enhancement. A decreased cervical lordotic curve was demonstrated in 2/3 cases. Accordingly, there were no enlarged retropharyngeal or cervical lymph nodes and no lytic bone lesions or vertebral fractures. The resolution of calcifications was not demonstrated due to the lack of followup radiographs. Resolution of symptoms on followup achieved early in two patients, and later than expected in another.

Summary of imaging studies.

| Nº | 1 | 2 | 3 | Ratio and mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plain radiograph | ||||

| Prevertebral calcification | – | – | N/A | 0/2 |

| Prevertebral soft tissue swelling | + | + | N/A | 2/2 |

| Decreased cervical lordotic curve | + | + | N/A | 2/2 |

| Contrast-enhanced CT | ||||

| Prevertebral calcification, vertebrae level | C1–C2 | C1–C2 | C1–C2 | 3/3 |

| Thickness of prevertebral soft tissues, mm | 10.4 | 11.8 | 12.7 | 11.6 |

| Decreased cervical lordotic curve | + | + | – | 2/2 |

| Retropharyngeal fluid collection, vertebrae level | C3–C5 | C2–C5 | C2–C5 | 3/3 |

CT, Computed Tomography; N/A, Not Available.

The literature review revealed relevant 153 articles, of which 114 were single case reports, 36 were case series containing 2–10 patients, and 3 were larger publications comprised of 12–45 patients. The total number of patients was 372, although this number may be biased as some cases may be repeated in several publications. Of these articles, 29 were published in radiology journals, 21 in orthopedic or rheumatologic journals, 17 in emergency medicine journals, 18 in neurology and pain journals, 12 in internal medicine journals, and 27 in otolaryngology journals. Twentynine articles were published in other journal types. Surgical or invasive procedures were mentioned in 13.7% of publications and were performed in 28 patients (see Supplementary document for complete detail). One patient was operated on because of concurrent laryngeal gout and not because of ALT.

DiscussionAcute longus colli tendinitis, also known as acute retropharyngeal calcific tendonitis and calcific tendinitis of the longus colli muscle, is caused by calcium hydroxyapatite deposition in the tendon of the longus colli muscle with subsequent inflammation. The characteristic clinical presentation includes the triad of acute neck pain, odynophagia, and painful limitation of neck range of motion.1,2

Historical viewTo the best of our knowledge, the first description in the English language literature was reported in 1964 by Hartley, who described the connection between the clinical symptoms and amorphous calcium deposits anterior to the atlantoaxial joint.3

The first publications in the non-English literature date tos the middle of the twentieth century. The first case to be detected on a plain radiograph was reported in 1950 by Krook and was published in the subsequent year.4,5 In his report, Krook noted the similarity of this condition to calcific tendinitis occurring in other locations. Fahlgren and Löfstedt published the first description of the syndrome in 1963 describing in Swedish their findings of ten patients,6–10 and in 1967 they were the first to correlate the presence of the amorphous calcifications anterior to the upper cervical vertebrae with the tendon of the longus colli muscle.11,12

The pathogenesis was clarified in 1994 by Ring et al.13 The initial misdiagnosis of the disease had led to unnecessary medical treatment in five patients and unnecessary open biopsy in one patient. The pathological evaluation demonstrated a foreign body inflammatory response secondary to the deposition of calcium hydroxyapatite crystals in the superior oblique tendon fibers of the longus colli muscle.

Although clinically relevant, reports of this entity in the otolaryngology literature are scarce.14–20 The earliest description of this entity we could find in the otolaryngology literature was published in January 1982 by Herwig and Gluckman.21

PathophysiologyThe underlying process of ALT is calcium hydroxyapatite deposition disease (CHADD) of the longus colli muscle at its tendon attachment to the C1 anterior tubercle, with secondary inflammatory tendinitis.16,18,22 This process may be similar to that of calcific tendinitis in other locations, commonly observed in the supraspinatus tendon of the rotator cuff, patellar tendon, and Achilles tendon.23 The precise cause of CHADD is unknown.24 It has been speculated that crystal deposition may occur following injury or repetitive trauma. A genetic predisposition, disorders of thyroid and estrogen metabolism, and metabolic factors also have been suggested to play a role.16,25,26 Reactive calcific tendinitis appears to occur in viable, not necrotic tissue, unlike dystrophic calcification.27 The relation of ALT to tissue ischemia and necrosis is controversial.16,27–29

Rui et al. isolated tendon-derived stem cells (TDSCs) from the flexor tendon and patellar tendon of rats.30 According to their model, erroneous differentiation TDSCs into chondrocytes or osteoblasts rather than to tenocytes may account for metachondroplasia and ectopic ossification in calcifying tendinitis. This may then cause aberrant deposition of extracellular matrix, resulting in mucoid degeneration and weakening of the tendon. Finally, ossification occurs, and the calcific deposition is formed. Since ossified tendons have increased stiffness, ossification can be perceived as a localized attempt to compensate for the original decreased stiffness of the tendon. This hypothesis is supported by the up-regulation of cartilage-associated genes and downregulation of tendon-associated genes in rat supraspinatus tendon.31

EpidemiologyThe condition affects adults within a reported age range of 21–81 years, with the highest distribution between 30 and 60 years.2,13,14,19,32 There is a 60 percent female predominance.2,19,26 No race or ethnicity is overrepresented.14,20 The estimated annual incidence is 0.5 cases per 100,000 person-years, with an age-matched incidence of 1.31 per 100,000 person-years.19 The true incidence of ALT remains unclear because it is probably frequently missed.2,11

Clinical presentationAccording to the review of the literature done by Park et al.26 the most common symptoms were neck pain (94%), limited range of motion (45%), odynophagia (45%), neck stiffness (42%), dysphagia (27%), sore throat (17%), and neck spasm (11%). The involvement of the longus colli muscle explains most symptoms, while dysphagia is thought to occur due to the anatomic proximity between the retropharyngeal space and pharyngeal constrictors.33

Examination, typically, reveals cervical paraspinal muscle spasm with the head held in slight flexion. The range of motion is extremely limited, usually secondary to severe pain, especially in extension.13 According to some authors, a fiberoptic endoscopic examination may show swelling of the posterior wall of the nasopharynx,20 although no such finding was observed in our study. Laboratory findings include a normal or slightly elevated white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein.26

Imaging studiesThe longus colli muscle consists of 3 portions: superior oblique, inferior oblique, and vertical. Classically, the calcification affects the superior oblique portion of the longus colli muscle and can be seen on imaging studies at the C1–C2 vertebrae levels,34 although calcification as low as the C5–C6 levels has also been described.18,35

Lateral neck radiographs may demonstrate prevertebral soft tissue swelling and an amorphous radiodensity 10–20 mm in diameter anterior to the first or second cervical vertebra. These radiological findings disappear as the symptoms resolve within 2-weeks.14

These calcifications are not always visible on plain X-Ray films, as seen in our sample. Moreover, other processes can mimic the calcifications of ALT on plain radiographs.11 For example, an inferior accessory ossicle of the anterior C1 arch, the inferior portion of the C1 arch, the C2 lateral masses on a rotated projection, and a calcified stylohyoid ligament can each be confused with an intra-tendinous calcification.11

Neck MRI detects inflammation involving the longus colli muscle by demonstrating high signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging in the retropharyngeal space. The MRI examination also permits excluding spondylitis and epidural abscesses or tumor. However, MRI is insensitive for the demonstration of calcification.13,34

The higher contrast resolution of computed tomography (CT) makes it a more sensitive technique than plain radiography or MRI for the detection of such calcification.20,34 CT is also more accessible and less expensive than MRI, thus making it the preferred first-line imaging modality.20

The overall frequency of ALT in CT of the neck is 1.1:1000 examinations. The frequency increases significantly to 11.4:1000 in patients without a history of recent trauma, suspected postoperative complication, clinical signs of deep neck infection, a known tumor of the neck region, or suspected metastatic spread from other locations.36

It is essential to demonstrate five key elements during CT interpretation34,37: 1) The effusion smoothly expands the retropharyngeal space in all directions; 2) absence of wall enhancement; 3) absence of suppurative lymph nodes in the retropharyngeal space; 4) demonstration of the pathognomonic calcifications in the superior oblique fibers of the longus colli muscle and 5) absence of bony destructive change to the adjacent cervical spine vertebrae. Failure to demonstrate these five key radiologic findings should lead one to suspect and evaluate an alternative diagnosis.

Evaluation and managementThe differential diagnosis focuses on excluding other more severe diseases before making the diagnosis of ALT. The approach to the patient is dictated by the patient’s history, physical examination, and imaging studies. When typical features of nuchal pain or spasm are accompanied by neurological signs or symptoms, the diagnosis of meningitis must be considered. Cervical deep space infections, especially retropharyngeal abscess, must always be considered in the differential diagnosis due to the strong resemblance of the clinical presentation and some similarities in imaging studies. Radiographs can show prevertebral soft tissue thickening but not the amorphic calcific density. When the typical calcification is not demonstrated on plain radiograph, CT offers higher sensitivity. CT may show effusion in both ALT and retropharyngeal abscess. However, ALT features include a more even expansion of the effusion in all directions, the absence of wall enhancement, lack of suppurative lymph nodes in the retropharyngeal space, and the pathognomonic calcifications in the superior oblique fibers of the longus colli muscle.33 The age of the patient must also be a consideration since ALT is described only in the adult population. Thus, a similar clinical presentation in a pediatric patient should raise suspicion for cervical deep space infections such as retropharyngeal or parapharyngeal abscess. If trauma has occurred, cervical soft tissue swelling, hematoma, fractures, and disc herniation are all possible. However, the presence of trauma can separate those patients.

Additionally, if there is a coincidental history of recent trauma, CT can rule out the possibility of an avulsion fracture since a bone fragment can be easily distinguished from the amorphous calcification associated with ALT. Spondylitis and spondylodiscitis are differentiated from ALT by the presence of bony erosions or destruction of the vertebral bodies, intervertebral space narrowing, and the lack of prevertebral calcifications in the acute settings. Additionally, associated lymphadenopathy may contribute to the distinction. Bony metastases should pose no diagnostic problem, and a lytic bone lesion or fracture would be clearly visible on CT. Foreign bodies in the upper aerodigestive tract usually present with a characteristic history, and radiographically are less likely to be as far superior as C1 to C2 in the prevertebral soft tissue. Edema in the retropharyngeal space may also occur as an expected side effect of therapeutic radiation to the area, or as a sequela to resection of a jugular vein from previous surgery.

TreatmentThe inflammation is self-limited, and complete resolution of symptoms usually achieved after 1–2 weeks.26,38,39 Symptomatic treatment typically consists of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with corticosteroids and opioid analgesics being reserved for more severe cases.2,20,26,29 Additional analgesia by other drugs may be added with or without opioids. Muscle relaxants and H2-blockers were used by some authors. However, randomized control trials are needed to determine the efficacy of medical treatment. A soft cervical collar may be used, although there is no evidence to support its application. Duration of treatment varies considerably between studies from less than one day to 5 weeks.

Antibiotics, local analgesic therapy, extracorporeal shock wave therapy, and surgical treatments are not indicated.29 Although the disappearance of calcifications may be demonstrated by a plane radiograph,16,38 followup imaging is not routinely recommended.40 Local recurrence has not been previously reported.29

ConclusionAcute longus colli tendinitis is an infrequent and underrecognized benign cause of atraumatic neck pain produced by inflammation of the longus colli muscle. Although the clinical manifestations can be difficult to distinguish from other more severe disorders, the diagnosis can be established by its pathognomonic imaging findings. Management is conservative with an early resolution of symptoms. Recognition of this self-limited condition by otolaryngologists can prevent misdirected medical therapy and unnecessary invasive procedures.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Associação Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia Cérvico-Facial.