Hearing loss may impair the development of a child. The rehabilitation process for individuals with hearing loss depends on effective interventions.

ObjectiveTo describe the linguistic profile and the hearing skills of children using hearing aids, to characterize the rehabilitation process and to analyze its association with the children's degree of hearing loss.

MethodsCross-sectional study with a non-probabilistic sample of 110 children using hearing aids (6–10 years of age) for mild to profound hearing loss. Tests of language, speech perception, phonemic discrimination, and school performance were performed. The associations were verified by the following tests: chi-squared for linear trend and Kruskal–Wallis.

ResultsAbout 65% of the children had altered vocabulary, whereas 89% and 94% had altered phonology and inferior school performance, respectively. The degree of hearing loss was associated with differences in the median age of diagnosis; the age at which the hearing aids were adapted and at which speech therapy was started; and the performance on auditory tests and the type of communication used.

ConclusionThe diagnosis of hearing loss and the clinical interventions occurred late, contributing to impairments in auditory and language development.

A deficiência auditiva pode comprometer o desenvolvimento infantil. O processo de reabilitação dos indivíduos com perda auditiva depende de intervenções eficientes.

ObjetivoDescrever o perfil linguístico e as habilidades auditivas de usuários de Aparelho de Amplificação Sonora Individual (AASI), caracterizar o processo de intervenção fonoaudiológica e analisar sua relação com o grau da perda auditiva das crianças.

MétodoEstudo transversal com amostra não-probabilística composta por 110 crianças de 6 a 10 anos de idade, com perda auditiva de grau leve a profundo, usuárias de AASI. Foram realizados testes de linguagem, percepção de fala, discriminação fonêmica e desempenho escolar. As associações foram verificadas pelos testes χ2 de tendência linear e Kruskal-Wallis.

ResultadosCerca de 65% das crianças apresentavam alteração do vocabulário, 89% de fonologia e 94% tiveram desempenho escolar considerado inferior. O grau da perda auditiva mostrou-se associado a diferenças nas medianas das idades de diagnóstico, de adaptação do AASI e de início da fonoterapia; do tempo entre diagnóstico e adaptação do aparelho auditivo; ao resultado dos testes auditivos e ao tipo de comunicação utilizada.

ConclusãoIndependentemente do grau de perda auditiva, o diagnóstico e as intervenções necessárias ocorreram tardiamente, com prejuízo das habilidades linguísticas e auditivas destas crianças.

Hearing loss is a high-prevalence disease, ranging from one to three per 1000 individuals; this number increases in the presence of risk factors for hearing impairment.1,2 Its main consequence, especially in children, is the impact caused by sensory deprivation in the development of auditory and language skills and learning. Any degree of hearing loss can result in significant damage, as it interferes with perception and understanding of speech sounds.3

In the national scenario, due to the social magnitude of hearing impairment prevalence and its consequences in the Brazilian population, the Ministry of Health4,5 instituted the Hearing Health Care Services (Serviços de Atenção à Saúde Auditiva – SASA) which, together with the Neonatal Hearing Screening Program, have as a goal the early diagnosis, intervention, and rehabilitation of individuals with hearing impairment.

The first years of life are considered critical for child development, as the peak of the central auditory system maturation process occurs during childhood and neuronal plasticity is at its maximum.6 This makes the early detection of hearing impairment crucial to minimize the damaging impact on the development of language and listening skills, as well as on the learning process caused by hearing loss.6–11

In addition to an early diagnosis, the literature also points out the importance of interventional speech therapy in the successful rehabilitation of children with hearing impairment.6,7 The earlier the diagnosis is established and auditory speech therapy is initiated, the closer development of affected children will be to that of normal hearing children.9,11

Thus, this study aimed to describe the oral and written linguistic profile and auditory skills of children using an individual sound amplification device (ISAD), fitted in the period 2008–2010 in a SASA, and to characterize the process of speech therapy intervention and analyze its association with the degree of hearing loss of the children.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional, observational study conducted in a high-complexity SASA in Belo Horizonte, state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, from September of 2011 to May of 2012.

After data collection from the service's database, 206 children treated in the years 2008–2010, who had an auditory diagnosis confirmed through pure tone and speech audiometry assessment, were identified.

Exclusion criteria included normal hearing, history of otorhinolaryngological surgery, treatment abandonment, transfer to another SASA, presence of syndromes and associated neurological alterations, and death; the eligible population consisted of 131 children. Of these, seven could not be located and 14 did not attend the evaluation. Thus, the population consisted of 110 individuals.

All 110 children were assessed individually for language and auditory skills, and during the evaluation they used the ISAD. The evaluation was performed in a single session lasting an average of 1h. Parents or guardians answered a structured questionnaire aimed to characterize the sample, with the following thematic axes: risk indicators for hearing loss at birth, data on auditory diagnosis, intervention and speech therapy/audiological follow-up, school life, and socioeconomic indicators.

The ABFW Child Language Test protocol,12 designed for children aged 3–12 years, was used for evaluation of oral language. It consists of evaluations in the areas of phonology, vocabulary, fluency, and pragmatics. This research used the phonology and vocabulary tasks. Only orally communicative children (n=80) were able to perform these tests.

For the vocabulary test, the recording of the children's responses immediately followed the naming, in individual sheets, and the criteria established by the test author were followed for the analysis.13,14

For the phonology assessment, this study used the spontaneous naming task. The recording of responses was carried out with a Cassio® Exilim digital camera, in movie mode. After listening to the file, the phonetic transcription and analysis of responses were performed. The recording of one child with moderately severe to severe hearing loss degree could not be recovered. The criteria established by the test author were followed for the analysis.15

The School Performance Test (SPT) was used to evaluate the written language16; it was developed for evaluation of schoolchildren from the first to the sixth grade of elementary school. It consists of three subtests: writing, arithmetic, and reading. The final classification of the SPT and of each subtest was performed as described by the author of the tool.17 To analyze the results of SPT test in the first graders, the middle-lower and middle-upper classifications were grouped in the “medium” category.

Two protocols were used to evaluate hearing skills: the Glendonald Auditory Screening Procedure (GASP)18 and the phoneme discrimination test with figures.19 The speech perception test – GASP – consists of five tests that evaluate the capacity of detecting Ling sounds, vowel discrimination, extension discrimination, word recognition, and comprehension of sentences using the ISAD. The test analysis was performed as suggested by the literature.18 This research also evaluated the overall test result by calculating the means of all tests in order to analyze the overall result and compare individuals.

The phoneme discrimination test with figures assesses the phonemic discrimination capacity through minimal pairs. The final score was classified as adequate or altered according to age, following the criteria proposed by the literature.19 A zero score was considered for those children who were unable to perform the test.

The analysis of the child's type of communication was divided into three categories: orally communicative, orally communicative associated with the Brazilian Sign Language (Língua Brasileira de Sinais [LIBRAS]; the child can express herself orally, but uses LIBRAS when he/she cannot communicate effectively), and non-orally communicative (LIBRAS user exclusively and/or functional gestures), according to the answer given by the parent/guardian on the questionnaire.

The auditory diagnosis was made according to the criteria established in the literature regarding degree and type.20 To analyze the variable degree of hearing loss, the diagnosis in the better ear was considered and the children were divided into three groups: mild to moderate; moderately severe to severe, and profound bilateral hearing loss. This study observed children with sensorineural, conductive, and mixed hearing loss in all three groups.

Data were stored in electronic files, with double entry and checking of the consistency of the database. The statistical package Epi Info 7.1.0.6 was used for data processing and analysis.

Descriptive analysis of the frequency distribution of categorical variables and analysis of measures of central tendency and dispersion for continuous variables was performed. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to verify the association between the degree of hearing loss and the aspects of speech therapy intervention and auditory performance in tests. The level of significance was set at 5%.

The chi-squared test for linear trend was used to verify the association between the degree of hearing loss and the type of communication used, comparing children with mild/moderate hearing loss to the others with more significant hearing loss.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, under Opinion No. ETIC 0316.0.203.000-10. All parents or guardians of the children participating in the study signed the informed consent (IC).

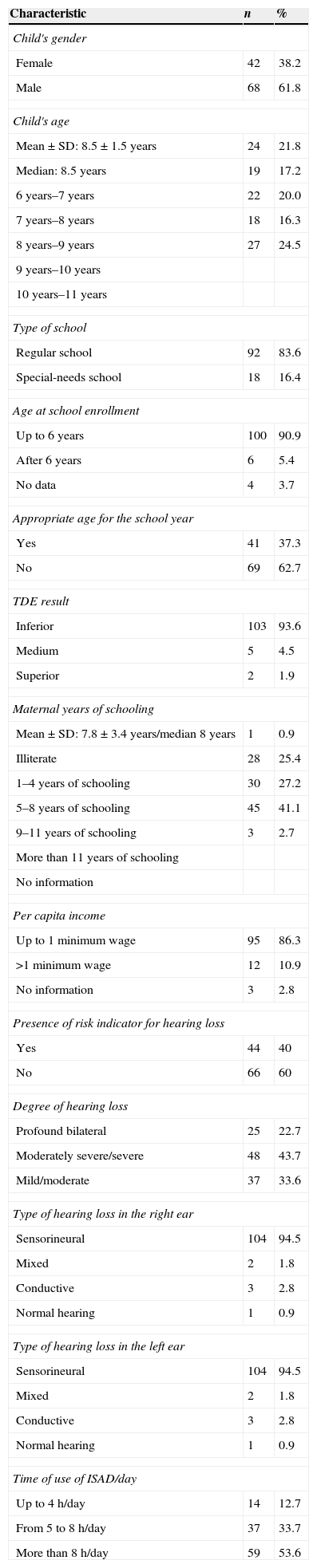

ResultsThe main characteristics of the 110 children evaluated in this study are described in Table 1.

General characteristics of the assessed children and their families.

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Child's gender | ||

| Female | 42 | 38.2 |

| Male | 68 | 61.8 |

| Child's age | ||

| Mean±SD: 8.5±1.5 years | 24 | 21.8 |

| Median: 8.5 years | 19 | 17.2 |

| 6 years–7 years | 22 | 20.0 |

| 7 years–8 years | 18 | 16.3 |

| 8 years–9 years | 27 | 24.5 |

| 9 years–10 years | ||

| 10 years–11 years | ||

| Type of school | ||

| Regular school | 92 | 83.6 |

| Special-needs school | 18 | 16.4 |

| Age at school enrollment | ||

| Up to 6 years | 100 | 90.9 |

| After 6 years | 6 | 5.4 |

| No data | 4 | 3.7 |

| Appropriate age for the school year | ||

| Yes | 41 | 37.3 |

| No | 69 | 62.7 |

| TDE result | ||

| Inferior | 103 | 93.6 |

| Medium | 5 | 4.5 |

| Superior | 2 | 1.9 |

| Maternal years of schooling | ||

| Mean±SD: 7.8±3.4 years/median 8 years | 1 | 0.9 |

| Illiterate | 28 | 25.4 |

| 1–4 years of schooling | 30 | 27.2 |

| 5–8 years of schooling | 45 | 41.1 |

| 9–11 years of schooling | 3 | 2.7 |

| More than 11 years of schooling | ||

| No information | ||

| Per capita income | ||

| Up to 1 minimum wage | 95 | 86.3 |

| >1 minimum wage | 12 | 10.9 |

| No information | 3 | 2.8 |

| Presence of risk indicator for hearing loss | ||

| Yes | 44 | 40 |

| No | 66 | 60 |

| Degree of hearing loss | ||

| Profound bilateral | 25 | 22.7 |

| Moderately severe/severe | 48 | 43.7 |

| Mild/moderate | 37 | 33.6 |

| Type of hearing loss in the right ear | ||

| Sensorineural | 104 | 94.5 |

| Mixed | 2 | 1.8 |

| Conductive | 3 | 2.8 |

| Normal hearing | 1 | 0.9 |

| Type of hearing loss in the left ear | ||

| Sensorineural | 104 | 94.5 |

| Mixed | 2 | 1.8 |

| Conductive | 3 | 2.8 |

| Normal hearing | 1 | 0.9 |

| Time of use of ISAD/day | ||

| Up to 4h/day | 14 | 12.7 |

| From 5 to 8h/day | 37 | 33.7 |

| More than 8h/day | 59 | 53.6 |

The degree of hearing loss was most frequently moderately severe/severe (43.7%). The most frequent audiometric curve was downward sloping (56.3% in the RE and 53.6% in the LE). The median time of hearing aid fitting of the children was 2.68 years (range 0.9–4.5 years).

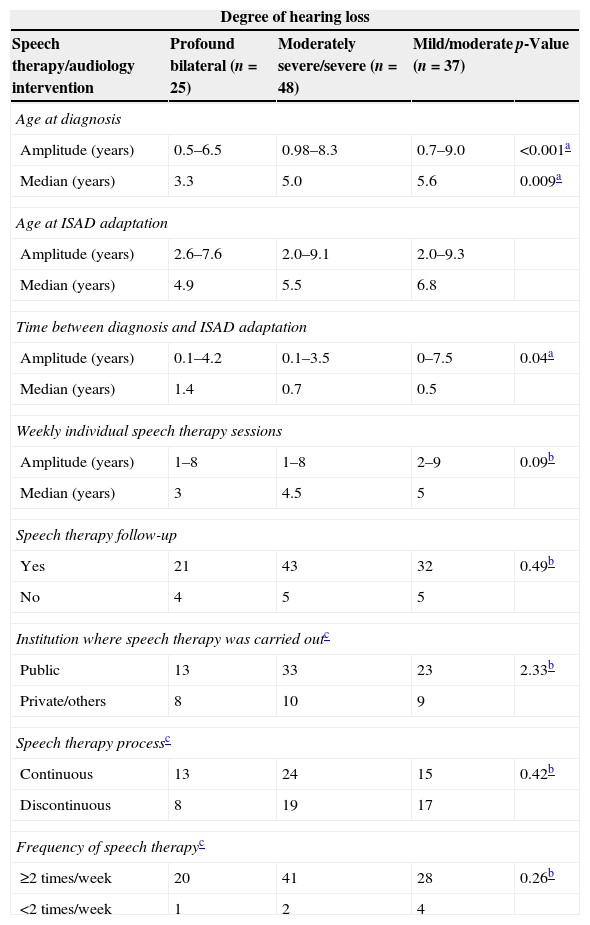

Table 2 describes aspects of the audiological/speech therapy intervention.

Aspects of speech therapy intervention according to the degree of hearing loss.

| Degree of hearing loss | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speech therapy/audiology intervention | Profound bilateral (n=25) | Moderately severe/severe (n=48) | Mild/moderate (n=37) | p-Value |

| Age at diagnosis | ||||

| Amplitude (years) | 0.5–6.5 | 0.98–8.3 | 0.7–9.0 | <0.001a |

| Median (years) | 3.3 | 5.0 | 5.6 | 0.009a |

| Age at ISAD adaptation | ||||

| Amplitude (years) | 2.6–7.6 | 2.0–9.1 | 2.0–9.3 | |

| Median (years) | 4.9 | 5.5 | 6.8 | |

| Time between diagnosis and ISAD adaptation | ||||

| Amplitude (years) | 0.1–4.2 | 0.1–3.5 | 0–7.5 | 0.04a |

| Median (years) | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.5 | |

| Weekly individual speech therapy sessions | ||||

| Amplitude (years) | 1–8 | 1–8 | 2–9 | 0.09b |

| Median (years) | 3 | 4.5 | 5 | |

| Speech therapy follow-up | ||||

| Yes | 21 | 43 | 32 | 0.49b |

| No | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| Institution where speech therapy was carried outc | ||||

| Public | 13 | 33 | 23 | 2.33b |

| Private/others | 8 | 10 | 9 | |

| Speech therapy processc | ||||

| Continuous | 13 | 24 | 15 | 0.42b |

| Discontinuous | 8 | 19 | 17 | |

| Frequency of speech therapyc | ||||

| ≥2 times/week | 20 | 41 | 28 | 0.26b |

| <2 times/week | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

There was a statistically significant difference between the median ages at diagnosis, age at hearing aid fitting, time between diagnosis and hearing aid fitting, and the initiation of speech therapy according to the degree of hearing loss.

There was no association between follow-up in speech therapy, the number of speech therapy consultations, continuity of the speech therapy process, and the type of institution the children attended for speech therapy according to the degree of hearing loss.

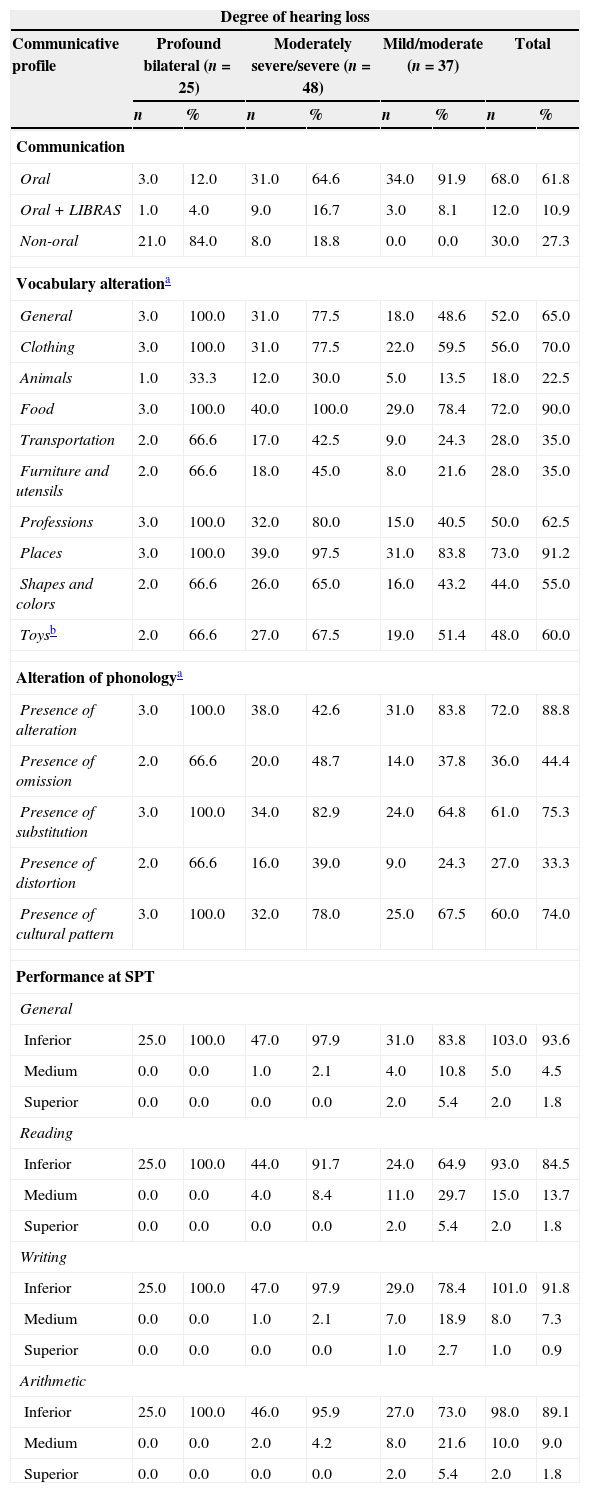

The distribution of the children according to the degree of hearing loss and the type of communication used, and the results of the oral language and writing tests are shown in Table 3.

Distribution of children according to the degree of hearing loss and the type of communication used, and results of oral and written language tests.

| Degree of hearing loss | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communicative profile | Profound bilateral (n=25) | Moderately severe/severe (n=48) | Mild/moderate (n=37) | Total | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Communication | ||||||||

| Oral | 3.0 | 12.0 | 31.0 | 64.6 | 34.0 | 91.9 | 68.0 | 61.8 |

| Oral+LIBRAS | 1.0 | 4.0 | 9.0 | 16.7 | 3.0 | 8.1 | 12.0 | 10.9 |

| Non-oral | 21.0 | 84.0 | 8.0 | 18.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 30.0 | 27.3 |

| Vocabulary alterationa | ||||||||

| General | 3.0 | 100.0 | 31.0 | 77.5 | 18.0 | 48.6 | 52.0 | 65.0 |

| Clothing | 3.0 | 100.0 | 31.0 | 77.5 | 22.0 | 59.5 | 56.0 | 70.0 |

| Animals | 1.0 | 33.3 | 12.0 | 30.0 | 5.0 | 13.5 | 18.0 | 22.5 |

| Food | 3.0 | 100.0 | 40.0 | 100.0 | 29.0 | 78.4 | 72.0 | 90.0 |

| Transportation | 2.0 | 66.6 | 17.0 | 42.5 | 9.0 | 24.3 | 28.0 | 35.0 |

| Furniture and utensils | 2.0 | 66.6 | 18.0 | 45.0 | 8.0 | 21.6 | 28.0 | 35.0 |

| Professions | 3.0 | 100.0 | 32.0 | 80.0 | 15.0 | 40.5 | 50.0 | 62.5 |

| Places | 3.0 | 100.0 | 39.0 | 97.5 | 31.0 | 83.8 | 73.0 | 91.2 |

| Shapes and colors | 2.0 | 66.6 | 26.0 | 65.0 | 16.0 | 43.2 | 44.0 | 55.0 |

| Toysb | 2.0 | 66.6 | 27.0 | 67.5 | 19.0 | 51.4 | 48.0 | 60.0 |

| Alteration of phonologya | ||||||||

| Presence of alteration | 3.0 | 100.0 | 38.0 | 42.6 | 31.0 | 83.8 | 72.0 | 88.8 |

| Presence of omission | 2.0 | 66.6 | 20.0 | 48.7 | 14.0 | 37.8 | 36.0 | 44.4 |

| Presence of substitution | 3.0 | 100.0 | 34.0 | 82.9 | 24.0 | 64.8 | 61.0 | 75.3 |

| Presence of distortion | 2.0 | 66.6 | 16.0 | 39.0 | 9.0 | 24.3 | 27.0 | 33.3 |

| Presence of cultural pattern | 3.0 | 100.0 | 32.0 | 78.0 | 25.0 | 67.5 | 60.0 | 74.0 |

| Performance at SPT | ||||||||

| General | ||||||||

| Inferior | 25.0 | 100.0 | 47.0 | 97.9 | 31.0 | 83.8 | 103.0 | 93.6 |

| Medium | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 4.0 | 10.8 | 5.0 | 4.5 |

| Superior | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 5.4 | 2.0 | 1.8 |

| Reading | ||||||||

| Inferior | 25.0 | 100.0 | 44.0 | 91.7 | 24.0 | 64.9 | 93.0 | 84.5 |

| Medium | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 8.4 | 11.0 | 29.7 | 15.0 | 13.7 |

| Superior | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 5.4 | 2.0 | 1.8 |

| Writing | ||||||||

| Inferior | 25.0 | 100.0 | 47.0 | 97.9 | 29.0 | 78.4 | 101.0 | 91.8 |

| Medium | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 7.0 | 18.9 | 8.0 | 7.3 |

| Superior | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| Arithmetic | ||||||||

| Inferior | 25.0 | 100.0 | 46.0 | 95.9 | 27.0 | 73.0 | 98.0 | 89.1 |

| Medium | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 4.2 | 8.0 | 21.6 | 10.0 | 9.0 |

| Superior | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 5.4 | 2.0 | 1.8 |

LIBRAS, Brazilian Sign Language; SPT, school performance test.

Regarding language, 65% of the children had below normal vocabulary and 88.8% had some abnormalities in the area of phonology.

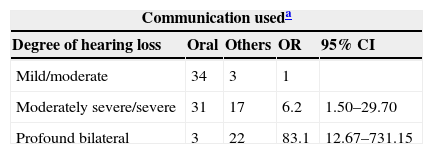

Table 4 shows the result of the association between the degree of hearing loss and the type of communication used by the children with hearing impairment.

Association between the degree of hearing loss and the type of communication used by children with hearing impairment.

| Communication useda | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of hearing loss | Oral | Others | OR | 95% CI |

| Mild/moderate | 34 | 3 | 1 | |

| Moderately severe/severe | 31 | 17 | 6.2 | 1.50–29.70 |

| Profound bilateral | 3 | 22 | 83.1 | 12.67–731.15 |

There was an association between the degree of hearing loss and the type of communication used by the child. The risk that a child with moderately severe/severe degree of hearing loss would not use oral language to communicate was 6.2 times higher than a child with mild/moderate degree of hearing loss; and the risk of a child with profound bilateral hearing loss of not using oral language to communicate was 83.1 times higher than a child with mild/moderate degree of hearing loss.

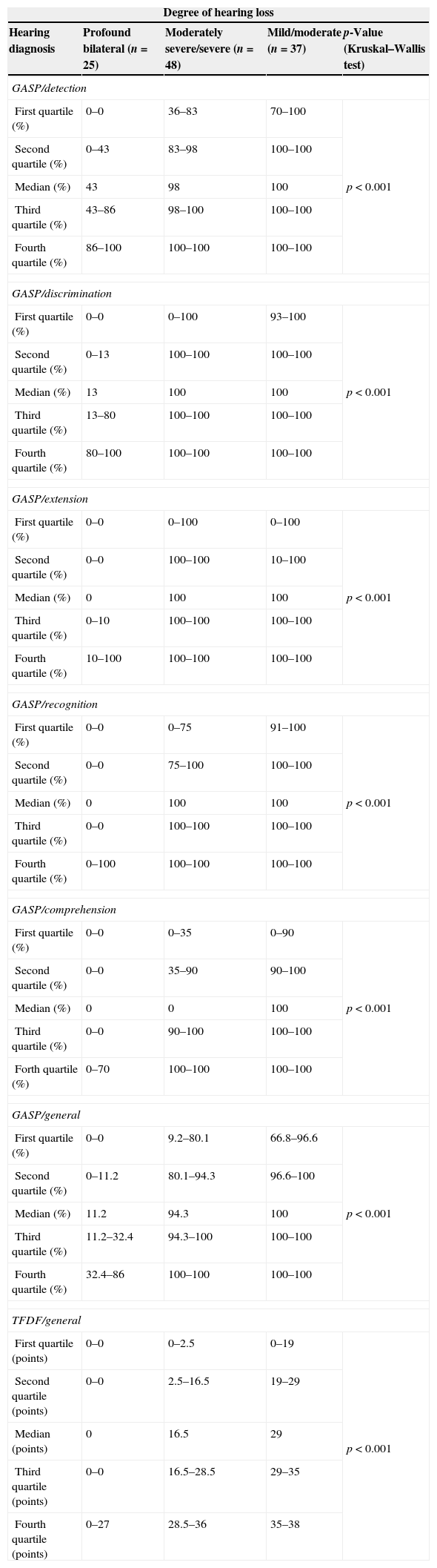

Table 5 describes the children's performance in the auditory tests GASP and the phoneme discrimination test with figures, according to the degree of hearing loss.

Performance of the eligible population in the hearing, GASP, and TFDF tests, according to the degree of hearing loss.

| Degree of hearing loss | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hearing diagnosis | Profound bilateral (n=25) | Moderately severe/severe (n=48) | Mild/moderate (n=37) | p-Value (Kruskal–Wallis test) |

| GASP/detection | ||||

| First quartile (%) | 0–0 | 36–83 | 70–100 | p<0.001 |

| Second quartile (%) | 0–43 | 83–98 | 100–100 | |

| Median (%) | 43 | 98 | 100 | |

| Third quartile (%) | 43–86 | 98–100 | 100–100 | |

| Fourth quartile (%) | 86–100 | 100–100 | 100–100 | |

| GASP/discrimination | ||||

| First quartile (%) | 0–0 | 0–100 | 93–100 | p<0.001 |

| Second quartile (%) | 0–13 | 100–100 | 100–100 | |

| Median (%) | 13 | 100 | 100 | |

| Third quartile (%) | 13–80 | 100–100 | 100–100 | |

| Fourth quartile (%) | 80–100 | 100–100 | 100–100 | |

| GASP/extension | ||||

| First quartile (%) | 0–0 | 0–100 | 0–100 | p<0.001 |

| Second quartile (%) | 0–0 | 100–100 | 10–100 | |

| Median (%) | 0 | 100 | 100 | |

| Third quartile (%) | 0–10 | 100–100 | 100–100 | |

| Fourth quartile (%) | 10–100 | 100–100 | 100–100 | |

| GASP/recognition | ||||

| First quartile (%) | 0–0 | 0–75 | 91–100 | p<0.001 |

| Second quartile (%) | 0–0 | 75–100 | 100–100 | |

| Median (%) | 0 | 100 | 100 | |

| Third quartile (%) | 0–0 | 100–100 | 100–100 | |

| Fourth quartile (%) | 0–100 | 100–100 | 100–100 | |

| GASP/comprehension | ||||

| First quartile (%) | 0–0 | 0–35 | 0–90 | p<0.001 |

| Second quartile (%) | 0–0 | 35–90 | 90–100 | |

| Median (%) | 0 | 0 | 100 | |

| Third quartile (%) | 0–0 | 90–100 | 100–100 | |

| Forth quartile (%) | 0–70 | 100–100 | 100–100 | |

| GASP/general | ||||

| First quartile (%) | 0–0 | 9.2–80.1 | 66.8–96.6 | p<0.001 |

| Second quartile (%) | 0–11.2 | 80.1–94.3 | 96.6–100 | |

| Median (%) | 11.2 | 94.3 | 100 | |

| Third quartile (%) | 11.2–32.4 | 94.3–100 | 100–100 | |

| Fourth quartile (%) | 32.4–86 | 100–100 | 100–100 | |

| TFDF/general | ||||

| First quartile (points) | 0–0 | 0–2.5 | 0–19 | p<0.001 |

| Second quartile (points) | 0–0 | 2.5–16.5 | 19–29 | |

| Median (points) | 0 | 16.5 | 29 | |

| Third quartile (points) | 0–0 | 16.5–28.5 | 29–35 | |

| Fourth quartile (points) | 0–27 | 28.5–36 | 35–38 | |

GASP, Glendonald Auditory Screening Procedure; TFDF, phoneme discrimination test with figures.

The mean age of the children evaluated in this study was eight years and six months; most of them attended regular school and had started school before age 6. At this age, the child is expected to be well-adapted at school and to have acquired an extensive vocabulary, to know the rules of syntax, and to have acquired all speech sounds.7,13,21 However, most of the study children did not achieve the expected results in the phonology and vocabulary test, regardless of the degree of hearing loss.

The assessed children showed a prevalence of moderately severe/severe hearing loss, with a downward sloping audiometric curve. This type of configuration can result in great deficits in receptive and expressive language, especially in discrimination and recognition of speech sounds, particularly fricative sounds.17,22

Regarding the type of hearing loss, the sensorineural type was the most often observed in this study. However, in some children, different types of hearing loss were found in each ear. In the sensorineural type, hearing loss is most often irreversible and the greater involvement occurs at the level of auditory comprehension.23 In the conductive and mixed types, hearing fluctuation may hinder speech intelligibility, and consequently, the child can develop phonological and auditory processing alterations, as well as learning difficulties.22

In the group of children with profound bilateral hearing loss, the age at the auditory diagnosis and the age at ISAD fitting were lower than in the other studied groups. This can be explained by the fact that profound hearing loss is more easily perceived by the family and health professionals involved with the child.24 Early referral favors the process of diagnosis and the fitting of the ISAD in a timely and efficient manner. However, in cases of less severe hearing loss, the child's difficulties can go undetected by health professionals and the family, and are often observed by teachers during the emergence of learning disabilities.6,23

The mean time between diagnosis and ISAD fitting, in general, was longer in the group of children with profound bilateral hearing loss, even though the age at diagnosis was younger in this group. For the auditory diagnosis of children younger than 3 years of age, it is necessary to perform more complex tests and procedures, such as brainstem auditory evoked potential and otoacoustic emission. The increased duration of the diagnostic step can be related to the greater number of audiological tests required for completion of diagnosis in these children.24

In this study, regardless of the degree of hearing loss, age at diagnosis and ISAD fitting occurred late, which is in disagreement with what is proposed in the literature, i.e., that the auditory diagnosis should be established before the third month of life and speech therapy intervention be started by 6 months of age.1,22,25

Some studies carried out in Brazil also showed that it was difficult to achieve the recommended standards. In a study that assessed the status of the diagnosis and care of patients with hearing loss aged 0–14 years in the city of Campinas, the mean age at diagnosis was 4.3 years and the mean age at ISAD fitting was 7.5 years.24 In the study that aimed to characterize the age at diagnosis and intervention of children treated at the Hospital das Clínicas de São Paulo, the mean age at these steps was 5.4 years and 6.8 years, respectively.6

These aspects of language intervention become relevant because the age at diagnosis and adaptation are determining factors for the prognosis of auditory and language skill development in children with hearing impairment.6 The Newborn Hearing Screening Program (NHSP) was implemented in the state of Minas Gerais through SES Resolution No. 1.32126 and became mandatory nationwide through Federal Law No. 12.30327 for early detection of hearing loss, due to the impact that hearing loss can have on child development. It is worth mentioning that the children evaluated in this study were not submitted to the NHSP, which may explain the results related to speech therapy intervention.

Regardless of the degree of hearing loss, the effective use of the electronic device alone most often is not enough to minimize the damage to the auditory and language skills, and speech therapy is of utmost importance in this process.21,28 According to the literature, the therapeutic process should be started as early as possible, be continuous, and involve the child's family.3

The results of the present study showed that most children using hearing aids were still waiting for speech therapy or were receiving an inadequate number of sessions. In the state of Minas Gerais, speech rehabilitation of hearing-impaired children should be guaranteed at least twice a week by SASA or by municipalities through decentralized speech therapists.4,5,29 The difficulty of access to speech therapy sessions was also mentioned in other studies, such as in the city of Salvador, in which the provision of speech therapy was by the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde [SUS])30 and another that investigated the characteristics of diagnosis and speech therapy intervention in children with hearing impairment in the city of Blumenau.31

The large number of children with below normal development of oral and written language and listening skills, regardless of the degree of hearing loss, reflects the consequences of speech therapy intervention for these individuals.

The development of speech perception auditory skills in the group of children with mild/moderate hearing loss were as expected. However, poor performance was observed in the phonemic discrimination task, and in the lexical and phonological development. It is expected that children with this type and degree of hearing loss, effectively using an ISAD and undergoing speech therapy intervention, will have development close to that of children with normal hearing.17

Moderately severe/severe hearing loss can have a greater impact on the development of auditory and language skills in children with hearing impairment when compared to those with mild/moderate hearing loss. However, the use of hearing aids and the stimulation of the auditory skills would allow these children a satisfactory hearing and oral language development.

In this study, a large number of children had significant difficulty in listening comprehension skills. As a result, many are not orally communicative, and among those who use speech to communicate, most of them showed great delay in lexical and phonological development.

For the group of children with profound bilateral hearing loss, no response was observed to the detection, discrimination, perception of extension, recognition and listening comprehension skills. Few children in this group used speech to communicate, and those who were orally communicative showed a significant delay in lexical and phonological development. The residual hearing observed in children with profound bilateral hearing loss is small, which limits the dynamic range of hearing and, consequently, the auditory gain with the ISAD, explaining the great difficulty these children experience in the perception of environmental sounds and speech.32,33

In these cases, the use of the cochlear implant is indicated; it has provided great benefits in language development in children with profound hearing loss, as it provides access to speech information, particularly at high frequencies, which is generally not possible with the use of an ISAD. Moreover, implanted children have better speech perception, increased number of produced vowels and consonants, and better speech intelligibility than those using hearing aids.28,32,33

However, for this type of intervention to be performed with satisfactory outcomes in the development of auditory and language skills, the hearing diagnosis and speech therapy intervention must be early.28,34

Regarding the performance of written language skills in all evaluated groups, the majority of the children had a low performance in the academic achievement test. This result may be associated with low performance in the auditory and oral language tests. It is common to observe learning difficulties in children with hearing impairment, as the deficits of oral language and auditory skills can have, as a consequence, changes in the development process of reading, writing, and logical and mathematical reasoning.

Moreover, the domains of capacity of symbolization, generalization, manipulation of sounds, and phonological awareness are also crucial in learning and are poorly developed in these children.35

The hearing and language impairments observed in these two groups could have been minimized if these children had been assessed by the NHSP and speech therapy intervention had been initiated early. The critical period of central auditory system maturation mainly occurs in the first five years of life.34 However, the age at diagnosis, ISAD fitting, and start of speech therapy found for these groups were after the age of 5 years. Additionally, socioeconomic factors can also influence children's development.3,36 In this study, most of the children came from families with per capita income below the minimum wage and the level of parental education was low.

The difficulty in the auditory skills of the assessed children, regardless of the degree of hearing loss, can also be seen in the discrepancy between the results of the two hearing tests. In all groups, the better results were observed in the GASP test than in the phoneme discrimination test with figures. This fact can be explained by the different auditory skills required in each test. The skills of detection, vowel discrimination, perception of extension, auditory recognition in a closed set, and comprehension of everyday sentences are involved the GASP test performance.

As for the phoneme discrimination test with figures, the auditory skill involved is phonemic discrimination of minimal pairs. For the child to have a good performance in this test, other auditory skills should also be mastered, such as temporal processing.19 Furthermore, the semantic and phonological components, phonological awareness, and memory involved increase the degree of the test difficulty for children with hearing impairment.19

Difficulties in auditory development, as well as oral and written language observed in the subjects of this study reinforce the importance of attention and care for children diagnosed with hearing impairment. After the implementation of the National Hearing Care Policy in 2004 by the Ministry of Health,4,5 these individuals now have access to full care, from the auditory diagnosis, provision of electronic sound amplification devices (hearing aids and cochlear implants), as well as speech therapy.

This is an innovative program that has brought great benefits to the treatment of individuals with hearing disabilities in Brazil. However, for all the proposed aims to be achieved, it is important that a restructuring in the Hearing Health Network occur in Brazil. Public policies should focus on network integration through initiatives in primary care, such as the training of health professionals regarding the suspicion and diagnosis of hearing loss in children, structuring of the newborn hearing screening program, and investments to qualify the SASAs and rehabilitation centers. Agile and efficient access of children to a hearing health program and the availability of experienced and qualified professionals to perform such functions should be guaranteed.

This study also highlights the importance of participation of a multidisciplinary team involved in the care of individuals with hearing impairment who integrate into SASAs, such as social workers and psychologists, both for the intervention and for family counseling. The involvement of the family in the rehabilitation process of children with hearing impairment is essential to achieve good results.3

Currently, the assessment of the hearing health service quality is directed toward infrastructure (physical facilities, number of professionals, equipment) and monthly procedure productivity, which does not guarantee the assessment of the quality of services provided. The periodic and standardized assessment of the auditory skills and language development in children followed in SASAs must be systematically conducted, aiding treatment planning as a resource to assess the quality of the intervention.

Thus, longitudinal studies are needed to monitor the quality of services and the advances of the national hearing health program proposals. The influence of some factors such as age, rehabilitation facilities, family, socio-economic environment, and the child's social behavior should also be investigated in order to implement more appropriate actions in the different loco-regional realities.

During the study performance, there was some difficulty in the selection of standardized and validated tools developed in Brazil for children with hearing impairment older than 6 years of age, especially for the assessment of oral language (vocabulary and phonology) and learning. In most cases, in the available assessments, normal values were based on the performance of children with normal hearing and, as the processes of hearing and language development of children with hearing loss do not follow the same standards, there was some difficulty when comparing with the results of other studies.

Regarding the development of phonology in children with hearing loss, very often the alteration observed was associated with the difficulty in perception and discrimination of speech sounds caused by the auditory acuity reduction. However, it was decided to evaluate this aspect of language development with the aim of investigating the exchanges and phonological processes observed in the development of the assessed children.

It is noteworthy that the effective use of ISADs, time of hearing aid fitting, and the time of speech and audiological therapy may also influence auditory development, as well as oral and written language. In this study, most of the assessed children effectively used hearing aids. However, there was a large variability in time of ISAD fitting and speech therapy among the individuals.

These variables may have influenced the development of the assessed children, as well as their performance in the tests.

ConclusionMany of the children with hearing impairment had abnormal development of auditory skills, oral language, and written language. This outcome is related to the characteristics of speech therapy, as the auditory diagnosis, the fitting of the ISAD, and speech therapy follow-up occurred late, regardless of the degree of hearing loss.

Evaluation of oral and written language and auditory skills of children with hearing impairment should be performed periodically, so that the process of speech therapy intervention may be reassessed and so the therapeutic strategy is planned in accordance with the evolution of each individual.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Penna LM, Lemos SM, Alves CR. Auditory and language skills of children using hearing aids. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;81:148–57.